The CSCSW Board and District Coordinators met in January in Santa Ana to discuss the strategic plan for the society.

THE CLINICAL UPDATE | WINTER 2020

Bipolar Not So Much: Understanding Your Mood Swings and Depression | Upcoming events

|

Letter from our President, Monica Blauner, LCSW

By Monica Blauner, LCSW

I’m very pleased to report that CSCSW continues to grow. Our membership is more diverse and increasing at a faster rate than it has in recent years. As we expand our benefits, we are gaining more student and ASW members. Our new board is also more diverse, with new energy and ideas for growing the organization to better serve you.

In our 50th year we are currently offering our first webinar series organized by the Education Committee. Online events allow people from all over the state, including those who do not live in active districts, to have access to our educational offerings. Our webinars and other filmed educational events will be available on the website for viewing, and in some cases will offer CEU’s. A special thank you goes to Rob Weiss for providing our first webinar series, and encouraging us to use technology to reach more of our colleagues.

In the spring, we will have two additional webinars on important topics, both by Barbara Griswold, MFT:

- Clinical Documentation - What’s Missing from Your Client Charts: Writing Great Progress Notes

- Insurance - What EVERY Therapist Should Know About Insurance — Even if You Want Nothing to Do With It.

In our efforts to both keep you informed and provide newly required training, we will be offering the 6 CEU training on Suicide Risk Assessment and Intervention in several districts around the state. LCSW’s will be required to document 6 hours of suicide prevention training prior to January 1, 2021. In Los Angeles, we had another successful collaboration with USC and had 124 attendees.

We have continued successful collaborations with other organizations. In Los Angeles, we have partnered with USC to offer the suicide prevention workshop above, and the licensing event Everything you need to know about becoming an LCSW: The BBS Speaks, which we will co-host for the third year this June. For the second year, we have also partnered with the San Fernando Valley Chapter of CAMFT to offer another workshop focused on diversity issues: Power, Privilege and Allyship in the Therapy Room. In Palo Alto, we jointly sponsored a suicide prevention training with the Concern, an employee assistance program.

One of the Society’s goals has been to increase diversity on the board and in our membership. Thanks to the efforts of board members Jaya Roy, Amanda Lee and Trish Yeh we now have the Diversity, Equity, and Transformation Committee, which will plan educational events and offer a clinical consultation group for people of color.

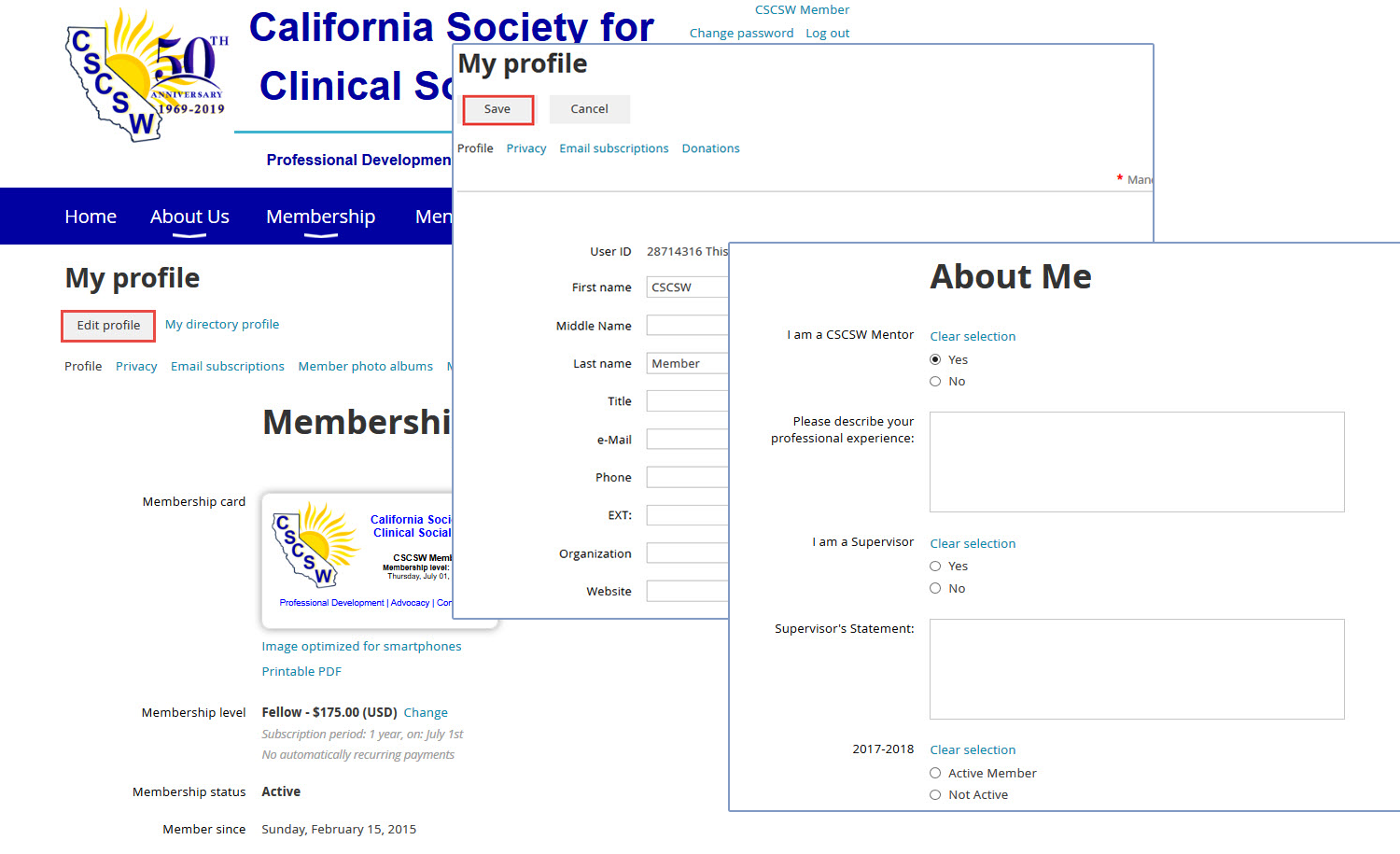

The Mentorship Committee, led by Jennifer Kulka, has revamped the Mentorship Match Process, so that potential mentees can view the profiles of available mentors. Please consider serving as a mentor to an individual or a group. If you haven’t done so already and wish to mentor please mark this on your online profile and include your areas of experience and interest. (See below - Tips for Updating your Online Profile)

The Communications Committee is actively working to increase our social media presence. Please be sure to connect with us by joining our closed, members-only Facebook Group, and follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn. Please share posts of our events with your colleagues.

We have a revived the Advocacy Committee, and its new chair, Jaclyn Escobar, represents CSCSW at BBS meetings. She provides updates to our membership on pending legislation, one of the priorities cited in last year’s member survey.

Also in response to the member surveys, we are providing several events related to private practice in San Diego, Sacramento Davis, and Los Angeles.

We are currently accepting applications for the Jannette Alexander Foundation (JAF) Scholarship. The scholarships are awarded to students at any California accredited graduate school of social work. The deadline for submission is March 1. Winners receive a $1000 award and a year’s free membership in CSCSW. In order to sustain this scholarship, its funds must be replenished. Click here to make a tax-deductible contribution to JAF today.

The focus of the last board meeting, held on January 11th, was strategic planning, led by our consultant, Golnaz Agahi. Your input is welcome!

"Suicide Assessment, Intervention, and Risk Management" will be presented by Kim Bozart, LCSW, on Saturday, April. 4, 2020 in San Diego. This in-person training will meet the new one-time mandatory 6-CEU requirement from the California Board of Behavioral Sciences (BBS) for Suicide Risk Assessment and Intervention training for LCSWs, LMFTs, and LPCCs renewing their license on or after January 1, 2021, as well as Associates applying for their LCSW, LMFT or LPCC on or after January 1, 2021.

|

|

BBS Updates:

1.) Custody of client records due to licensee death or incapacitation:

- Many states have requirements on this for psychotherapists, ranging from including a plan of action in the informed consent before providing services, to maintaining an alternate, as well as other options.

- Since there is no current California statute on this topic, yet it has grave implications, the board has decided to do further research on this topic as well as to encourage feedback from stake holders.

2.) Continuing Education Audits:

During this most recent year, 26% of LCSWs failed the continuing education audits. Please make sure that your CEUs are conducted by approved vendors.

Legislative Updates:

1.) Licensing

This bill decreases barriers for inter-state licensure. It allows a pathway for LCSWs and other professions who are actively licensed in another state, and have been for at least two years, to become licensed in California. Effective January 1, 2020. Below is the full law: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB679

2.) Required Notice

This bill mandates all psychotherapists to provide, prior to initiating services, a printed notice disclosing where to file a complaint about the therapist. Effective July 1, 2020. For more information, below is the full law: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB630

Below is an example of the required notice:

The Board of Behavioral Sciences receives and responds to complaints regarding services provided within the scope of practice of clinical social workers. You may contact the board online at www.bbs.ca.gov, or by calling (916) 574-7830.

3.) Supervision of Associates & Trainees

This bill allows clinical social workers to gain a maximum of 1,200 hours gained under the supervision of a licensed educational psychologist providing educationally related mental health services that are consistent with the scope of practice of an educational psychologist. Effective January 1, 2020. For more information, belowis the full law: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200AB1651

4.) Required Reporting to Licensing Board

This bill requires any health care facility or other entity for which a healing arts licensee practices to make a report to the applicable licensing board within 15 days of receiving any allegations of sexual abuse or sexual misconduct against the licensee by a patient, if the patient or a patient’s representative makes the allegation in writing. Effective January 1, 2020. For more information, below is the full law: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB425

5.) 90-Day Rule

“90-day rule” is a clause in the law that allows applicants for registration as an Associate Clinical Social Worker (Associate), whose Associate application is received within 90 days of the qualifying degree award date, to count supervised experience gained during the window of time between the degree award date and the issue date of the Associate registration number. Effective for MSWs graduating on or after January 1, 2020.

6.) Suicide Risk Assessment and Intervention

Under this law, applicants for licensure and licensees must have completed a minimum of six hours in suicide risk assessment and intervention through one of the following:

- coursework during your graduate program

- applied experience under supervision, or

- continuing education.

- Effective January 1, 2021. For more information, find the full law at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB1436

Additional Reading:

Laws require health plans to provide patients equal treatment for mental and physical needs. But "parity" is often elusive — and critics say the Legislature and health officials have failed to fix the problem. Full article: https://calmatters.org/projects/california-mental-health-care-parity/

Using Play Therapy to Treat Trauma

Using Play Therapy to Treat Trauma

By Jeanette Harroun, LMFT, RPT-S

“Enter into children’s play and you will find the place where their minds, hearts and souls meet.” (Virginia Axline).

Play therapy is an evidenced-based treatment primarily used with children ages three to twelve. It is a developmentally appropriate way to help children explore and express thoughts and feelings, often non-verbally. Play therapy starts with genuine acceptance of the child. The therapist encourages creative play, intervening (setting limits/boundaries) only when necessary to provide structure and limits and maintain safety.

Human beings love to play, and our enjoyment is actually part of the brain’s hardwiring. We are designed to seek out activities that are enjoyable and play certainly fits the bill. It is also a survival mechanism that serves the adaptive purpose of facilitating learning and increasing the connections between the upper (executive) and lower (autonomic) parts of the brain.

Trauma also affects brain development, but in ways that are diametrically opposed to those of play. Trauma reduces the number of upper and lower brain connections, negatively impacts thinking and problem-solving skills, and increases reactivity (fight or flight). This results in behaviors such as tantrums, nightmares, irritability and aggression; or it causes internalization such as physical symptoms, depression and trouble focusing.

Healing Aspects of Play

Play therapy provides healing by giving children a way to become aware of feelings and express them in positive ways, as well as enhance their problem-solving skills. When used to treat trauma, it provides a means for children to externalize whatever is on their minds and make sense of traumatic events and experiences in their own time. Play therapy also can help increase a child’s communication skills and support trauma processing by creating links between memory and language. It works through the projection of unresolved feelings and thoughts onto toys or through sand or other media where they can be accessed, understood, processed and resolved in a physically and emotionally safe way. Because play feels safe and fun, it also encourages children to stay engaged in what might be an otherwise overwhelming and frightening process.

Play Therapy Approaches

Play is a rich source of information about the child’s overall developmental functioning, coping strategies and sense of self. It provides a means of assessing symptoms and responses, providing treatment and measuring progress. And it supports healing by providing children with a sense of freedom and a way to externalize their story.

Therapeutic play uses both non-directive (child-centered) and directive approaches. Directive play activities, including medium-specific activities such as art and sandtray, are structured and led by the therapist. They are typically problem-focused and action oriented. Non-directive play (child-centered play), based on the work of Virginia Axline, is based on a belief that children can work through and resolve their own issues given the opportunity and a supportive environment. In non-directive play, the child leads, choosing toys and activities that create a sense of self-advocacy and safety; an experience that trauma has taken away. Intervention in the play only occurs when necessary to provide structure and limits, and to maintain safety. Limits are set to protect the child, therapist, toys, and the room.

Determining which approach and interventions to use is based on the purpose (assessment or treatment, for example), the child’s needs, and the therapist’s training and competency. It is helpful to have training in both. Directive and non-directive play can both be used within a single session; however, it is important to be clear with the client which approach is being used.

Intervention Tool Box

In many ways play interventions are like household tools – no one tool is right for every job. Having an array of interventions to choose from is important in order to meet the client’s needs and provide appropriate support. These may include sensory and grounding interventions useful for soothing and embodiment.

Trauma is often an “out of body” experience meaning that the mind and body may disconnect from each other as a survival mechanism to prevent the experience from becoming completely overwhelming. When interventions are used for embodiment, it is to bring the child back into conscious awareness of their thoughts, feelings and physical sensations allowing them to integrate them into a healing whole. Grounding for example, is often used with dissociating clients to bring them back into the present moment by establishing a reconnection between mind and body.

Medium specific, directive or non-directive interventions may be chosen to provide a developmentally appropriate approach to trauma material. Tools are chosen to provide the best means to address the concerns that brought the child to therapy as well as any additional issues (dissociation or stagnant play for example) that may arise during the session.

An array of tools - art, sand, toys, sensory materials and activities can all be immensely useful. Play and art can be used to help children identify thoughts, feelings and beliefs about an event or series of experiences. They may help the child to calm down, soothe their physiology and increase their ability to regulate affect and behavior, while broadening their sense of self and increasing feelings of mastery. They are also useful in allowing a means for specific trauma memories to be brought into conscious awareness to be processed and integrated verbally and non-verbally so that healing occurs.

The sandtray is one of my favorite modes of play therapy. Sand has both creative and soothing qualities and can be used in either directive or non-directive play. Children are drawn to the sand, often burying their hands in it, using it as “snow” or “rain” or building scenes and worlds. Sandtray play is often dynamic and many times children will “narrate” their story as they play, allowing them to verbalize feelings and thoughts. Others use the sand for self-soothing. One six year old client, with a background of family trauma and anxiety, initially displayed high levels of frustration and anger when things did not go as expected: paint splashing, block towers falling, or seeing that a previous client had rearranged the dollhouse. Tracking and naming his feelings while playing in the sandtray gave him a means to identify and express his feelings. Now when he begins to feel upset or unsettled, he runs to the tray, burying his hands and allowing the sand to run through his fingers or over his arms until he feels better.

Another five year old client used sand to explore and work through issues related to early medical trauma. He had been born with several non-genetic birth defects and had been through multiple surgeries since birth. Although he was medically capable and did occasionally use the toilet, he resisted it and refused to be potty trained. Initially he was nervous about coming to therapy but responded positively to child-centered play. He loved to build and spent several sessions constructing towers with multiple passageways that he drove small toy cars through, although he worried (often aloud) that they would fall down and “break things.” He eventually made his way to the sandtray where he created a creature (he called it a spider) with wet sand and tubes. At this point he began to show a more conscious awareness of his own fears about bathroom use, expressing them by describing both the “spider’s” worries about not being able to go to the bathroom and his desire to help the spider feel better. Eventually he began to help the spider by pouring water through the tubes to show the spider “going potty.” This aligned with his own greater awareness of and willingness to identify when he needed to go to the bathroom.

Expressive arts interventions - whether non-directive or specific activities such as coloring feelings and creating self-portraits - are another way to encourage identification of sensations, emotions, thoughts, self-perceptions and understanding of family relationships. It is always interesting and informative to see what colors children associate with specific feelings. One client created an “inside/outside’ portrait of herself that used bright, happy colors on the outside and dark, sad colors on the back; this helped her share and process feelings about the unexpected loss of her step-father with whom she was close. Other uses of expressive arts can be to help clients understand and make connections between their physical selves and their feelings as a first step in greater self-regulation.

Finally, stories, roleplay and puppets are also wonderful ways to help children understand and process feelings, particularly around trauma. Bibliotherapy, particularly when combined with storytelling and play activities can be very powerful in this regard. Books such as Brave Bart (a story about a cat) are useful in helping to create an understanding of the feelings and fears engendered by trauma; while stories such as The Invisible String help children process loss and find resources for connection in other areas of their life. In one case, a young client struggling with attachment and abandonment issues after her parents’ divorce decided to create a series of paper bag puppets that she linked together to represent her missing family members (father and step-family); a tangible version of her “invisible string” that increased her feelings of connection to the family members (particularly her father) whom she longed for but rarely saw.

Specific Issues in Treatment

Two issues that often arise in trauma treatment are how and when to manage aggressive or stagnant play. Therapists are often concerned about aggressive play and possible re-traumatization; however it may be more detrimental to intercede too quickly. That doesn’t preclude setting appropriate limits, but in order to do so in a therapeutic way it is important to clearly identify and understand what is happening in the play.

Aggressive Play

Aggressive play differs from and is often confused with violent play. Differentiating between the two can provide a new perspective and understanding of how the child thinks and feels. Aggressive play is often an expression of anxiety and anger. Violent play is focused on the intent to harm. Children engaged in violent play often become angry, cry, hit and exhibit great distress. Aggressive play is more about playing energetically. Children engaged in active, “aggressive” play are more likely to be typically smiling and enjoying themselves. There is give and take to the play even though activities may include physical engagement (sword fighting, toys engaged in battle and the like). Limits are always set on unsafe play activities.

Typically, concerns and discomfort with aggressive play has more to do with our personal comfort zones and perspectives on aggression. A child smashing two trucks together may be their representation of a car accident. It is aggressive but not necessarily violent. So, while observing and tracking aggressive play may feel uncomfortable to the therapist, it is often beneficial to the child that we accept this kind of play as part of exploration and learning. This is supported by research that shows that aggressive play benefits children by helping them to learn what is acceptable and how to manage anger and other big feelings. Conversely, discouraging or attempting to redirect or end aggressive play has been shown to have a negative impact on the development of social, emotional, physical and communication skills. Supervision or consultation to help us understand the behavior and strengthen our limit setting skills can go a long way in creating greater comfort with aggressive play.

Stagnant or “Stuck” Play

Stagnant or “stuck” play is also an oft-expressed concern, and again it is important to be aware of our own concerns to avoid intervening too quickly.

Stagnant play is identified as an on-going observation of intense, ritualistic play behaviors and activities using the same materials over and over across the course of several sessions. During the session the child remains self-absorbed, often playing with little visible change of expression or evidence of pleasure. Carefully observing play and looking for even the smallest change is critically important as these are indicators of shifts in the play. If these are missed, it can lead to unnecessary intervention. If needed however, there are a number ways to help children reconnect mind and body and create distance and space in their story so they can move past whatever is blocking them. Non-directive interventions include verbal reflection and narration, and mirroring, as well as tracking of play content, behavior and affect. These can also be used in directive play along with wondering aloud (“what would happen if…”) and providing gentle redirection including offering options of other scenarios.

In summary, play therapy is very useful in treating trauma. It is fun and spontaneous; the activities encourage embodiment and the materials themselves are soothing. When used to assess and treat trauma it works to counteract many of the effects of trauma. While challenges can occur in treatment, there are also many interventions the sensitive therapist can use to mitigate negative impacts.

| Jeannette Harroun, LMFT, RPT-S has a private practice in Lafayette, CA. She specializes in working with children, teens and families to help them build stronger relationships and address concerns including anxiety, self-regulation, attachment, trauma and parenting. Her play therapy training includes child-centered play, sandtray and filial therapy, as well as parent education. She is a supervisor at the Wright Institute and also offers play therapy training classes. She can be reached at jeannette@bayarea-counseling.com or at (925) 890-7478 |

References:

- Brown, Stuart, MD (2009) Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination and Invigorates the Soul, New York, NY, Penguin Group

- Gil, Eliana (1991) The Healing Power of Play, New York, NY, The Guilford Press

- Goodyear-Brown, Paris (2010) Play with Traumatized Children, Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons

- Green, E. J., & Myrick, A. C. (2014, April 28). Treating Complex Trauma in Adolescents: A Phase-Based, Integrative Approach for Play Therapists. International Journal of Play Therapy. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0036679

- Hall, Jennifer Geddes. (2019, April). Child-Centered Play Therapy as a Means of Healing Children Exposed to Domestic Violence, International Journal of Play Therapy, 28(2), 98-105.

- Karst, Patrice and Lew-Vriethoff, Joanne (2018) The Invisible String

- Kennedy-Moore, Eileen, Ph.D. (2015) Do Boys Need Rough and Tumble Play? Psychology Today on-line publication. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/growing-friendships/201506/do-boys-need-rough-and-tumble-play

- Levine, Peter A, Ph.D. (2008) Healing Trauma, Boulder, CO, Sounds True, Inc.

- Oaklander, Violet, Ph.D. 35th anniversary ed. (2015) Windows to Our Children, Gouldsboro, ME, The Gestalt Journal Press

- Solomon, Marion F and Siegel, Daniel J., Eds. (2003), Healing Trauma: attachment, mind, body and brain, New York, NY, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Sheppard, Caroline H. (1998) Brave Bart: A story for traumatized and grieving children

by Leah Niehaus, LCSW

The developmental work of adolescence is clinically rich and vital to successful transition to adulthood, healthy connections, and life satisfaction. In this article, I explore the form and potential of adolescent group therapy. This will be a brief overview of a topic that requires more depth to fully understand and implement.

There are many aspects to the group process that I enjoy bearing witness to: connection amongst unlikely adolescents or isolated teens, altruism (you gain through helping others), universality (you are not alone), a corrective family experience, improved social skills, learning from each other, identity formation in relation to others, and the magic of group cohesiveness/belonging that provides light and hope for troubled youth. There is a particular place for clinical social workers in this modality—groups have a practical, down-to-earth approach, are strengths-based and holistic in nature, require authenticity of the leader, effect more individuals in the same ninety minutes, and offer a lower-cost alternative to families struggling to cover rising individual therapy costs or that have no health insurance.

The main developmental tasks of adolescence include: Separation- Individuation from parents, Identity-Formation (gender, career, sexual orientation, racial/ethnic/religious identity), Establishment of Peer Group, and Emerging Sexuality and Establishment of Intimacy (cv.sduhsd.net, 2019 ). Most teenagers spend the majority of time with their peers and they rely on other adolescents to help them accomplish their developmental tasks, which makes group therapy an ideal environment for support and change. Within the group therapeutic context, adolescents can work through the four main identity questions: Who am I? With whom do I identify? What do I believe in? Where am I going? (Leader, 1991). The group, which provides a container and support for members, comes to be felt as a “mother group” and becomes a transitional object for troubled teens (Scheidlinger, 1974).

In general, the literature is lacking on the benefits of adolescent group therapy and the specific differences that group therapy provides to teens versus individual/family therapy models—however, many of us intuitively know that our clinical work is truly more of an art than a science. It is hard to measure effectiveness and yet it is useful to still try. One study analyzed 56 outcome studies from 1974-1997 and found that the average adolescent treated by group treatment is better off than 73% of those in control groups (Hoag & Burlingame, 1997). We know that adult process groups have achieved success (think of the Alcoholics Anonymous model, Domestic Violence support groups, Batterer’s Treatment groups etc.) and that many of those successes are likely occurring in adolescent group therapy models as well, even if not well researched at this point. In recent years, I have noticed a rise in CBT and DBT group therapy options for teens in our South Bay area in Southern California...and groups have been used for years in psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment centers, substance abuse programs, and schools. Anecdotally, I have witnessed the group holding environment to be hugely positive for many adolescents that I have worked with over the years. There is something transformative about sharing your pain and struggles in a group setting, particularly for adolescents as they are hard wired to belong and establish strong peer connections.

The following are my thoughts and considerations from my experience conducting groups in a private-practice setting over the last few years. Many of these ideas are important to consider about group therapy, no matter what setting you are employed. A disclaimer: my recent groups have been Open-ended, Adolescent Girls’ process groups (separate Middle School and High School aged groups), that were dynamically oriented with primarily depressed, anxious, quirky, introverted, sensitive girls, some with internalizing behaviors and some with externalizing behaviors, mixed sexuality orientations, and in a middle class to upper class community. I have run these groups on my own, as I’ve been in a solo private practice setting (have had support and guidance from my consultation groups). Some girls have been in group for a short period and some have remained much of their high school experience. I have definitely adjusted parts of my process over time, made mistakes, and learned some lessons the hard way so I will share my general tips below.

Develop Group--Type of Group, Goals of Group, Theoretical Orientation, Open-Ended or Closed Group

Some groups are Task-oriented (ex. CBT Anxiety reduction group) and some are Process-oriented (ex. High school process group, dynamically oriented). This decision should largely be based on the needs of the clients, clinician’s style, personality, training, goals of group, and setting. Task-oriented groups or CBT/DBT groups may lend themselves to a Closed Group (meaning fixed number of weeks for the group to exist) and short-term goals and time frames. Process-oriented groups tend to be longer-term and open-ended. As a clinician, it is important to be mindful of the theoretical thrust of your particular group—many orientations can be utilized to run an effective group—CBT, DBT, Psychodynamic, Social Learning Theory, Strengths-Based, Trauma Theory, or Psychoeducational. The general goals of group therapy are to create safety among members, decrease problematic behaviors and feelings, relieve isolation, and establish peer connections.

Group characteristics: Size, One gender or Mixed gender, Balance/timing/personalities

In general, it has been suggested that eight group members is optimum (Yalom, 1985). In my experience, between six to eight members is ideal and allows for group cohesion, energy in the room, and balance of personalities. A group can start with as few as three members, if the plan is to continue to add more members as the referrals come in.

It is helpful to have some heterogeneity in terms of grade, age, and level of maturity. Separating younger adolescents from older adolescent is wise as there are major differences in what middle school students need and discuss versus high school students. However, within those groups, it is useful to have a range of ages, grades, and personalities. Depending on the type of group, there will be pros and cons to having a one gender or mixed gender group. I have enjoyed having girls’ groups, as they often discuss themes around their sexuality/boundaries/decision making that might be altered if boys were in the room. However, mixed gender groups offer different opportunities for the teens to discuss, empathize, and practice their social skills with the opposite gender.

The balance of group members is important to keep in mind. Over time I have found that it is helpful to have a variety of personalities at the table—a mix of introverted, extroverted, mature, immature, a variety of diagnoses, varied family constellations, and a range of intelligence/motivation/interests. This makes for interesting conversations, increased opportunities to empathize with one that is different from you, and a chance for learning from one another when they all have different skill sets. It is important to consider “goodness of fit” with each new group member, keeping in mind that some with budding personality disordered traits may be difficult to incorporate into group (or certainly not too many with complicated personality issues would be tricky). Clinicians should consider timing in their process, when to begin/end group and when to incorporate new members. Group cohesion will be impacted by these important considerations.

Screening/Intake process:

It is well worth your time to do a thorough bio-psycho-social-spiritual assessment before permitting a new adolescent to join your group. In my experience, a brief telephone screening with the teen/or parent will give you an idea of whether the adolescent will be an appropriate referral for your group. If the teen seems a fit from the details gathered over the phone, I then schedule an Intake session with adolescent and parent to review history, sign consent and release forms, go over the goals and rules of group, review confidentiality (between therapist and client and importance of confidentiality between group members), and review reporting laws. This is often my opportunity to hear the parent’s concerns and observe the interaction between the adolescent and their parents. During this session, I assess for ego strength, mental status, level of sophistication/character to insure that there is enough commonality to be a strong addition to the group.

Before an adolescent begins group, I contact outside collaterals that are working with the teen or family. It is important to know their observations, goals for group treatment, and whether the adolescent has any strange/anxious behaviors that might impact the other group members. Further, it is important to review pertinent IEPs, psychological evaluations, and hospital records to provide a clear clinical picture. Once a teen has begun group, it would be clinically harmful to not allow them to continue treatment (thus it is extremely important to do your due diligence before allowing them into group).

During the Intake session, discuss the importance of attendance and commitment to the group and how group members come to depend upon one another. Finally, the clinician should outline the parameters of how/when the therapist has contact with the parents. In recent years, I have begun emailing the parents a general summary of themes covered on a monthly basis. This doesn’t break confidentiality, but alerts them to the important topics that we are covering. Lastly, we look at the Group Contract and sign the agreement together.

Role of Leader:

“Being an adolescent group therapist is demanding…Of great importance for adolescent group therapists is a specific awareness and alertness to detect countertransference tendencies and reactions in themselves. They must also be able to tolerate the frustrations and lack of immediate positive results that is incumbent in treating adolescents due to their emotional volatility and experimental behavior” (Leader, 1991). Adolescent group therapists wear many hats, all in the space of one group session—limit setter, educator, parent, container of safe environment, therapeutic role, and instiller of hope. One must be authentic, genuine, and comfortable with one’s self. Clinicians must know how to manage affection and sexuality when working with adolescents—and know how to address these tricky gray areas with vulnerable youth.

In my experience, one of the most important tasks of the adolescent group therapist is to foster belonging. These are often the teens that have poor social skills, don’t get invited to birthday parties and sleepovers, are the black sheep in their families, and spend much of their time feeling isolated (whether it is real or imagined). Fostering a sense of belonging is key in healing. In my groups, we have snacks and make hot tea; we celebrate birthdays and the birthday person picks their desired treat; we create comforting rituals, such as weekly check-ins, passing out inspiration cards at the end of each group, and incorporating breathing/relaxation/mindfulness/setting intentions. If a teen is struggling and has been hospitalized or sent to residential, we make cards for them. If it’s been a particularly heavy group session, we end with something hopeful and a group hug. They always leave feeling like they belong in group. When an adolescent has achieved more success and stability, then we celebrate their graduation from group and have some rituals associated with that ending/new beginning.

The Group Life Cycle:

There is a rhythm with an established group that is healing and optimistic in and of itself. The concept of the five stages of adolescent group therapy is a helpful way to conceptualize the process. Members can move in and out of different stages fluidly. The first stage is the initial relatedness, which addresses group expectations and engagement. Next, the group develops into the testing of limits—a normal extension of the teen’s developmental task of separation and individuation. The therapist provides the space needed to explore and challenge. The third stage focuses on resolving authority issues, where the adolescents often question the group norms and rules, without penalty. The fourth stage is the work of self; during which therapists can decrease their role and let the adolescents assume more responsibility for their group and discussion. The final stage of the group is the moving on stage. Group members consolidate their learning, process feelings of termination, and internalize the feelings they had belonging to this group (Dies, 1996). As a clinician, it is truly remarkable to watch this process and be part of this process with youth.

References

- (cv.sduhsd.net, 2019). Developmental Tasks of Adolescence.

- Dies, D. R. (1996). The Unfolding of Adolescent Groups: A five-phase model of development. In P. Kymissis & D. A. Halperin (Eds.), Group therapy with children and adolescents (pp. 35-53). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

- Hoag, Matthew J. & Burlingame, Gary M. (1997). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Child and Adolescent Group Treatment: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, Vol. 26, No. 3, p. 234-246.

- Leader, Elaine (1991). Why Adolescent Group Therapy? Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy, Vol. 1, No. 2, p.81-93.

- Scheidlinger, Saul (1974). On the Concept of the “Mother-Group.” International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Vol. 24, Issue 4.

- Yalom, Irvin D. (1985). The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 5th edition, New York, NY: Basic Books.

| Leah M. Niehaus, LCSW has a private practice in Hermosa Beach, CA. Her website is www.leahmniehaus.com. She can be reached by emailing at leahniehaus@me.com or 310-546-4111. |

Exploring Internal, Interpersonal and Transpersonal Resources through Sociometry and Expressive Arts

Exploring Internal, Interpersonal and Transpersonal Resources through Sociometry and Expressive Arts

by Paul Lesnik, LCSW, TEP

Helping our clients to build and maintain resources is a significant aspect of the therapeutic journey. Every day, as a social worker, I assist clients to build inner resources or link them to more tangible resources to help them navigate their world. Resourcing is the underpinning of many interventions, including Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), the metaphor-building of hypnosis, and all trauma recovery frameworks. Resourcing is essential in moving clients through difficult situations into the grace of healing.

Resources are available in three arenas: Internal Resources – the strengths and tools of living that have been built internally over time; Interpersonal Resources – people from the past, or for many, the people in the present, including their therapist; and Transpersonal Resources – such as God, a Higher Power, Jesus, Buddha, etc. For others this resource is a universal energy, or an abstract that is helpful to them, such as the ocean, or nature in general.

People have support available in all categories, although often access is blocked, either intentionally or unconsciously. Our job as a guide in the world of resources is to help clients examine the choices they have made or have limited themselves to, and assist them in opening up to an expanded resource repertoire.

Sociometry explores the choices we make and how these choices either bring us closer to or farther away from connection to others. We are sociometrists as therapists whenever we help our clients examine the choices they make, and the resulting satisfaction they have with their lives as a result of their choices. In a group, sociometry makes apparent an invisible web of connection; the more we make the invisible connections between group members visible, the more opportunity they have to be connected to each other and as a group. This aids the clients in co-creating the group as a safe container necessary for taking personal risks and doing their therapeutic work.

Using resources as a jumping off point is just one way of helping group members connect. This is an exercise that can be used with a group, a family, or in an individual session, especially where clients have a difficult time recognizing their resources, or have blocked access to them.

Designate three locations on the floor, with some distance in between. A pillow, a scarf, or even a piece of paper can be used to mark these locations. The first location is for Inner (or intra-psychic) Resources or strengths. The second is for Interpersonal Resources (the people they consider resources). The third is for transpersonal resources (God, nature, spirituality, etc.) This creates what in sociometry is called a Locogram, a choice designated by a location.

Explain to participants that we all have a default arena of resourcing. Ask them to imagine a time of challenge and think about where they go first: inward, to others, or to a transpersonal resource for assistance. Then have them go to that place and share why they choose it.

The exercise can take participants in many directions. Often in a room of caregivers, there is a self-reliance that is second nature and so they choose internal resources first. In client groups they may have learned a deep mistrust of others, so they choose this category for quite a different reason. Others may be cut off from themselves and have a reliance on others to assist them in figuring out their challenges. And a third group may first go to a Higher Power or other transpersonal entity (such as going to the beach), having put their faith in a position of power during difficult times. You will see there are many justifications – some that may surprise you and them – in where people default.

After everyone has shared their reasons for their default, have them move to the place they would most like to explore, and share why they have chosen it. This will move participants to a future projection of resources other than their default. You may want to then move into action explorations, such as psychodrama or human sculpture.

You may bring this understanding to individual therapy to help your clients access their under-used resource area. Some questions to ask might be: who or what is keeping you from connecting to the resources that are available to you? Who harmed you or thwarted your belief in (other people, God, yourself)? What myth (or demon) do you live with that you may wish to discard? Each answer is a marker for delving deeper.

Example: In a group at a Drug and Alcohol Treatment Center clients were asked to participate in the Resourcing Exercise. Of the eight participants in the group, all but two chose the category of Inner Resources, many commenting they only had themselves, as they had “burnt bridges” to most of their Interpersonal Resources in their addictive behaviors.

One group member chose the Interpersonal location, stating, “I never learned to do anything on my own, I rely on my mother for everything.”

And one member, the lone choice for Transpersonal Resources, stated, “I have always had a strong connection to God, and I feel God was the one who brought me through two overdoses.” Many other group members stated they were envious of this relationship, as their God had abandoned them.

When participants were asked to choose a category they wished to develop, the sociometry shifted significantly. All but one person moved from Inner Resources, three to Interpersonal, and two to Transpersonal. The person who stayed in place in Inner Resources stated, “I have caused too much pain to the people I love for them to ever forgive me, and neither will God.” Those who shifted to the other categories sited their need to rebuild trust with their family members, or to find a path to spirituality now lost to their addiction.

In every movement in the exercise clients were able to visually see the connection they have to others, and to mark where a potential alliance in their healing may be. A client chose to do a small action vignette where they en-roled one of their fellow group members as an ideal, forgiving Higher Power. In the enactment the client found that the path to this connection may not be as difficult as they thought. Group members shared their hope that they too may find the path back to self, others, or a spiritual resource. The exercise led to forming clearer objectives for each one of the participant’s treatment plans; and the clients had already begun an emotional investment in these directions from their group experience.

Other ways to explore resources would be to have participants draw their idealized world that is rich with resources in all categories and then to look at the barriers – real and imagined – that block their spontaneity and creativity to use these resources. Their drawing creates an image vehicle that can be taken into action as a human sculpture, vignette, or full psychodrama.

It is my belief, supported by significant research in trauma healing, that, as we say in psychodrama, “We are both wounded and healed in connection to others.” Healing is co-created in the therapeutic relationship and in the strengthening of support internally, inter-personally and trans-personally. There is power in strengthening each of these arenas, so that when one is challenged, the others arise.

|

Paul Lesnik, LCSW, TEP, is a Clinical Social Worker and Psychodrama and Expressive Arts Trainer based in San Diego. He works in many Expressive Arts modalities, including Psychodrama, Sandplay and Soul Collage® with clients. He conducts training groups for clinicians and mental health professionals in infusing the arts into their practice. He is the only Board Certified Psychodrama Trainer in San Diego County. He has presented nationally on many topics, most recently on Exploring Gender Identity as an Aspect of Spirituality, Scene Setting in Psychodrama, and Exploring Identity Development through the Arts. He can be reached at paul.lesnik@gmail.com 619-780-7670 digdeepertherapy.com |

Is Splitting Families a Form of Psychological Torture?

Is Splitting Families a Form of Psychological Torture?

By Diane Perlman, Ph.D.

Separation from loved ones is a primal fear for any age, but strongly impacts the development of the young. While our policies of splitting families are described as child abuse, they seem more akin to psychological torture and a crime against humanity.

Mental health professionals are gravely concerned about the known effects of tearing children away from their parents who have made extraordinary sacrifices to protect them. This includes deportation of family members — leaving children and other loved ones bereft and traumatized, as well as the stress of living in constant fear of deportation. We are horrified, helplessly witnessing our government inflicting pain and psychologically damaging vulnerable people. Reckless endangerment and reckless indifference are policy, doing great harm and no good, qualifying as “political malpractice.”

On the mall in DC on July 4, 2019, I overheard someone say, “They’re not spoiled like those kids in the detention camps.” This attests to the success of psychological manipulation and disinformation preying on people’s susceptibility and sense of grievance. Our policies show psychological ignorance, a profound lack of empathy, impaired feeling function and even sadistic tendencies. They demonstrate antisocial behavior, denying the basic humanity of others. Mean-spirited officials incite fear to whip up their political base and to deter others.

There is a consensus among therapists, researchers, practitioners, and expert witnesses about the savagery of these mindless, punitive policies. We have worked with and studied adults who have suffered throughout life from harm done by early childhood separations and trauma. These unwise policies are creating a public health crisis.

Studies of children of deployed military parents show a drop in grades, higher risks for mental health and behavioral problems, drug use and suicide. And this is for children remaining in their homes, with other family members and friends, with no change in school, country, language, food, TV, and physical comforts. It is orders of magnitude more cataclysmic to be removed 100% from all that is familiar and to be subjected to total loss, profound grief, confusion, helplessness, hunger, thirst, crowding, uncleanliness, sickness, fear and human cruelty.

It is urgent beyond measure to stop separations and deportations and to reunite these families immediately. Harm deepens every passing day. Young children do not have our concept of time or sense of permanence. For them the present is an eternity. Children go through stages of intense protest, followed by despair, detachment and psychic numbing. Parents experience intolerable agony compounded by not knowing where their children are, how they are, or if and when they will see them again. Reunions after such separations are beset with a host of difficulties in recovering from trauma and rebuilding primary bonds.

Lights for Liberty Rally July 12, 2019 Lafayette Park DC, Remembering the children who died in detention. Photo by Diane Perlman

Psychological impacts include the following:

Erosion of Basic Trust. According to psychologist Erik Erikson developing an early sense of basic trust, the sense that the world is predictable and trustworthy, is the most important building block in one’s development. These separations undermine parents’ ability to fulfill their most important function, providing a foundation in trust for healthy development.

Attachment Disorders. Extensive research highlights the critical importance of a secure attachment pattern to become a well-functioning adult who can contribute to society. Disruptions to secure attachment can cause lifelong suffering and impairments with negative consequences to society.

Trauma. Producing intolerable stress and psychic pain beyond one’s capacity to cope is causing irreparable harm, extreme prolonged tension, profound grief, excruciating anguish, fear, and moral outrage.

Toxic Stress and Pathology. These brutal separations, including infants and toddlers, produce a range of physiological and psychological pathologies affecting brain development and coping mechanisms leading to personality disorders, PTSD, behavior problems, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, relationship disorders, dissociative disorders, stress-related physiological disorders, cognitive disorders and more. The administration is condemning vulnerable people to a lifetime of flashbacks, nightmares, anxiety attacks, health problems, cognitive deficits, impaired function, relationship problems and more.

Retraumatization. For those who fled from danger and oppression, took risks, made treacherous journeys across borders and continents with children, left loved ones and their culture to reach safety to protect their children, this is a retraumatization which compounds the devastation. People are deprived of the comfort from their closest bonds we naturally seek in the face of any trauma. Shockingly, some enforce a policy of no hugging in which staff cannot comfort screaming children, and even forbidding a brother and sister to hug after being taken from their parents.

Generational Transmission of Trauma. Effects of trauma tend to be passed down to future generations. It will affect the future parenting style of these children and the trauma can reverberate through future generations. The severity of the impact can be mitigated with safety, intensive, high quality trauma-informed therapy, detraumatization techniques, apologies, other healing and corrective life experiences and a good support system.

Vicarious Trauma. The phenomenon of “Vicarious Traumatization” refers to the effects experienced by counselors and others who witness the suffering, fear, trauma and all harm done to others as we watch these heart-wrenching separations in horror. We feel helpless and ashamed for the actions of our government.

Perpetration Induced Traumatic Stress (PITS). PITS, observed and coined by Rachel MacNair, PhD past president of The Society for the Study of Peace, Conflict and Violence, refers to the traumatic effects on the perpetrators who are following orders to commit these cruel acts, including the law enforcement officers hearing peoples’ screams as they carry out their inhumane orders.

Societal Consequences. Those escaping danger, fear, and poverty, who would likely become grateful, loyal, and patriotic residents and contributing members of society, are betrayed. Justifying these cruel policies fuels mean-spirited elements of our culture that dehumanize immigrants and create a social norm in which it is acceptable to punish and traumatize innocent people because “the law is the law,” it’s their fault for coming, and that it is legitimate to harm people to deter others.

Unconscious Historical Legacy. Separating children from families has been a dark part of American history beginning with genocide of Native Americans, abduction of Africans for use as our slaves who were raped and separated from their children and families, to the internment of Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor, and deporting beloved family members, even under Obama.

Punimania™. Punimania™ is a diagnostic term coined by me (Diane Perlman). This compulsion to punish is pathological and deserves a diagnosis. Punimania refers to the mindless pathological compulsion to punish when the punishment (1) does not address the true cause of the problem, (2) does not correct the problem, (3) causes suffering of innocent people over time and (4) causes harm even to the punisher, and (5) causes harm to the fabric and collective psyche of society.

Proposal: Psychological Trauma (PT) is the intentional infliction of suffering without resorting to direct physical violence.

Almerindo E. Ojeda defines Psychological Torture (PT) in What is Psychological Torture? (http://humanrights.ucdavis.edu/resources/library/documents-and-reports/ojeda.pdf) as follows:

All instances of PT must satisfy four criteria :

- Suffering

- Infliction

- Deliberateness

- Lack of direct physical violence (indirect physical violence is always present with torture).

Categories of Psychological Torture:

- Isolation: solitary or quasi-solitary confinement.

- Debilitation: food, water, and sleep deprivation; extreme temperatures

- Spatiotemporal disorientation: confinement in small places, natural light denial

- Sensory deprivation: hoods, goggles, gloves, deodorizing masks

- Sensory assault: shouting, loud music, bright lights.

- Desperation: indefinite detention, sense of futility.

- Threats: of death or violence, to self or others, mock executions, witness torture.

- Degradation: verbal, nudity, personal hygiene denial, overcrowding, contact with pests, or excrement, sexual, ethnic, religious.

- Pharmacological manipulation: tranquilizers, hallucinogens.

Does splitting families and the experiences these vulnerable people are forced to endure qualify as psychological torture? You decide.

Our Obligation to treat to heal. Although these divided families are deeply scarred by this trauma, studies of trauma survivors show that appropriate, effective treatments, including techniques of detraumatization by qualified, compassionate, ethical professionals can help reduce the severity of lifelong symptoms and consequence, and reduce the intergenerational transmission of trauma.

We urge immediate reunification of families and the provision of safety, stability, and basic human needs. In addition to individual, family and group therapy, collective healing will be supported by public recognition of this trauma, bearing witness, apology, some forms of restitution, emotional support and engagement in community life, and a variation of “truth and reconciliation” processes.

Maya Angelou said, “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

| Diane Perlman, PhD is a clinical and political psychologist, the US Convener of Transcend, International, former co-chair of Psychologists for Social Responsibility’s Task Force on Global Violence and Security, Visiting Scholar at George Mason University School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, and founding member of the Transcending Trauma Project, a former nursery school teacher, mother and grandmother. |

Advance Directives: The Delicate Intersection of Social Work Systems

By Tracy Greene Mintz, LCSW

Starting with the Karen Quinlan case in 1985 and followed by Terri Schiavo’s public family feud in 2003, Americans have been riveted by the sordid tales of heartbroken families fighting over healthcare decision-making. Although these two famous cases have been flashpoints for the right-to-die debate, buried in the subtext is whether or not the patient herself had made any healthcare wishes known; and if so, how.

In both cases, and certainly in millions of others, the patient who requires life-sustaining treatment is purported to have told someone what medical interventions and quality of life they would have wanted, but never bothered to write it down or appoint someone to speak on their behalf. If they had, would they have had different outcomes? One would think so, but this is not necessarily always true. In the recounting of these cases, reporters interviewed family members, clergy, doctors and lawyers. Why not social workers?

Healthcare decision-making is the perfect cross section of what I call the three pillars of social work: Advocacy, Mental Health, and Information & Referral. This area is also ripe with legal and ethical implications and shines a spotlight on our credo, first do no harm. Completing an advance healthcare directive seems to be the ultimate example of self-determination, one of our core values. In my practice area, nursing homes, this task is almost universally assigned to the social service department. In federal nursing home regulations, helping a resident with advance care planning falls to us.

First, the law. Healthcare decision-making is a legal process more than a medical one. That is confusing for many families. The laws pertaining to healthcare decisions are found in California Probate Code. As I tell my students, healthcare decision-making is a matter of state law, not federal. As social workers, we need to know where to look (information and referral) when helping clients (advocacy) record their wishes. They do this to achieve some peace of mind (mental health) as they face age and debility. California Probate Code states that an adult with capacity may complete a healthcare directive, and that a doctor decides if they have capacity.

We are not lawyers, so we can’t give legal advice but we still want to advocate for our clients to have their voices heard in their life and death healthcare matters. We can always refer to a probate or estate attorney, but we have to bear in mind the financial resources of our clients might be limited. Advanced healthcare directives are available from most doctors’ offices and hospitals and can be completed with two witnesses totally free of charge. All social workers need to be aware that for a nursing home resident who wants to complete a healthcare directive, the ombudsman must be one of the witnesses. There are no exceptions (CA Probate Code 4675).

Similarly, we aren’t doctors, but we want to help guide the conversations through any number of medical situations that may occur, and help our clients decide how they might want to handle those. We can always refer to a doctor or other medical professional for clients who have complex questions or scenarios they want to investigate. As for the mental health portion, I speak from experience after 20 years working in geriatric healthcare: when a health crisis occurs and people do not have their affairs in order, and when end-of-life choices must be made without the voice of the client, family systems are taxed sometimes beyond what they can handle.

This can raise ethical dilemmas about who is the identified client, what are our employer’s policies on advance directives, and countertransference feelings when client choices differ from our own.

Often, clients already have some documents in place but they really don’t know what they have. It is our responsibility to know how to read these and to guide clients, families and medical teams appropriately. Some clients have a General Power of Attorney. Many of these forms contain language explicitly stating, “This document does not authorize anyone to make medical decisions,” but the client and their surrogate have never read that so they think it gives them broad powers over a person’s whole life. Another common problem with existing documents is that most health care directive forms contain a sentence about when the agent’s authority goes into effect. The simple checking of a box can start or stop someone from intervening in their loved one’s medical decision. Finally, social workers need to know how to read all the pages of these documents to determine if they are valid. For example, Conservatorship papers from the Probate Court should say, “Conservator of the person,” and they should be orders, not investigation or filing forms.

Ever the problem-solvers, if we suspect a concern with the healthcare decision-making paperwork someone presents to us, we need to know what to do. You may refer them to your organization’s legal department, if available, or to an outside attorney, the Probate Court self-help desk, or a low-cost legal clinic. It’s always a stressful time when these documents must be accessed, so telling someone their documents are invalid or questionable, can make things much worse. The most important tasks are to focus on the identified client, promote self-determination, and validate family care and concern.

Cultural considerations are another social work skill that is very valuable in this area. The desire to get one’s affairs in order is a heavily white, western concept. The notion that one can control every aspect of the living and dying processes disregards many religious teachings and cultural beliefs. Social workers are adept at helping clients navigate the practical considerations of medical and legal systems while supporting diverse, client-centered interventions. So even though advance healthcare directives may seem outside our scope of practice, helping clients navigate multiple systems while promoting self-determination and dignity at the end of life are most certainly within our scope of expertise.

Resources:

- The California Attorney General’s Office offers free Advance Healthcare Directive forms in English and Spanish oag.ca.gov

- https://www.cdc.gov/training/ACP/page33994.html (Quinlan case)

- https://www.deathwithdignity.org/states/california/

- CMS State Operation Manual, Appendix PP, F74

| Tracy Greene Mintz, LCSW, has been working with older adults and their families across settings from hospital to home since 1999. She is a nationally recognized expert in Relocation Stress Syndrome/Transfer Trauma in seniors. Her company, Senior Care Training, offers social work consultation to over 125 health and residential care facilities in California and beyond. She has a small private practice based in Redondo Beach. |

Psychiatric Advance Directives – PADs

This information is from the National Resource Center on Psychiatric Advanced Directives – https://www.nrc-pad.org

About PADs

- A psychiatric advance directive (PAD) is a legal document that documents a person’s preferences for future mental health treatment, and allows appointment of a health proxy to interpret those preferences during a crisis.

- PADs may be drafted when a person is well enough to consider preferences for future mental health treatment.

- PADs are used when a person becomes unable to make decisions during a mental healthcrisis.

California Q and A

Ten commonly asked questions about PAD’s for California

Please note: the following 10 FAQs are designed to provide a quick and accessible guide to what California Statutes say – or do not say – about PADs. The FAQs do not attempt to provide a complete picture of the law in your state, nor can they take the place of legal advice. The answers were accurate when written in October 2006.

1. Can I write a legally-binding psychiatric advance directive (PAD)?

Yes. California’s Health Care Decisions Law allows you to appoint an agent to make decisions about your treatment if you become incompetent to make decisions; write instructions about how you would like your health care to proceed; or both. This law covers all types of health care, including psychiatric treatment. Protection & Advocacy, Inc has published a helpful guide for consumers, which includes the latest version of the statutory Advance Health Care Directive (AHCD) form. This form is not mandatory but is highly recommended. Protection & Advocacy also offers a detailed Trainer’s Manual on the subject of AHCDs. The state of California maintains a central registry of Advance Directives, which you may wish to use but is not mandatory. Click here for more information on that program.

2. Can I write advance instructions regarding psychiatric medications and/or hospitalization?

Yes. The statute allows you to set out your instructions on any aspect of your health care treatment, which could include advance decisions about psychiatric medications and/or hospitalization. The statutory AHCD form gives a variety of prompts for you to state your instructions in the event of a crisis (for example, you could state that you would prefer to remain in a quiet room). If you wish, you may make advance decisions to refuse medications and/ or hospitalization. If you do this, however, note that that state law may require your hospitalization in an emergency, even if you have declined it in your instructions.

3. Does anyone have to approve my advance instructions at the time I make them?

No. However, the document containing your advanced instructions must be notarized, or signed by two witnesses. Neither witness can be an employee of your health care provider, and one must be a non-relative. If you are a patient in a “skilled nursing facility”, meaning a facility providing skilled nursing care on a long term basis, your form must additionally be signed by a Patient Advocate or Ombudsman.

4. Can I appoint an agent to make mental health decisions for me if I become incompetent?

Yes, in one of two ways:

(1) You may appoint an agent (called a “surrogate” in California), using your AHCD. Your agent must be someone other than an employee of your health care or community care provider, unless he/she is also related to you. If you have a conservator under the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, you must seek the authorization of an attorney before appointing an agent.

(2) If you are already being treated in a health care facility, you may designate a surrogate to act during your current stay, for a maximum of 60 days in total. To do this, you need only inform your health care provider. The person nominated in this way has priority over any agent you already nominated in an AHCD, but only during that particular period of treatment, or 60 day period in total.

5. If I become incompetent, can my agent make decisions for me about medications, and/or hospitalization?

Yes, with some exceptions. In general, once you are determined to be incompetent (see below) your agent may make decisions about anything that you could decide on if you were competent. However, your agent cannot consent on your behalf to your commitment to, or placement in, a mental health treatment facility; nor can he/she consent on your behalf to psychosurgery, electroconvulsive treatment (ECT), sterilization or abortion. If you wish, you may use your AHCD to limit your agent’s authority to a certain type, or types, of decision.

6. Does my agent have to make decisions as he/she thinks I would make them (known as “substituted judgment”), or does he/she have to make them in my “best interests”?

Your agent must exercise substituted judgment to the extent that he or she can do so, based on your advance instructions and/or on your preferences as known by the agent. If it is not possible to make a decision in that way, your agent must make the decision in your best interests.

7. Is there any rule that says that I can only make advanced instructions, only appoint an agent, or that I must do both?

No. You may do one, the other, or both.

8. Before following my PAD, would my mental health care providers need a court to determine I am not competent to make a certain decision?

No. The California statute allows you to choose when your AHCD must be followed. Your AHCD will be followed when your primary physician determines that you do not understand the benefits and/or risks of a particular mental health care decision. Alternatively, you may state on your form that your AHCD should be followed at all times, whether or not you are competent to make decisions.

9. Does the statute say anything about when my mental health providers may decline to follow my PAD?

Yes. Your providers must decline to follow your AHCD if they would violate professional standards in doing so, or for “reasons of conscience”. In these situations, your provider must assist in trying to find another provider who will follow your AHCD. Additionally, your providers could decline to follow your AHCD if you became subject to compulsory treatment or hospitalization under California law.

10. How long does my PAD remain valid?

Your AHCD is valid as long as you do not revoke it. If you wish, however, you may specify an expiry date for your AHCD.

Spotlight on Ginny Frederick, LCSW

Spotlight on Ginny Frederick, LCSW

By Joan Berman, LCSW

For over 30 years, Virginia (Ginny) Frederick has provided leadership as a Coordinator of the Mid-Peninsula District of the California Society for Clinical Social Work (CSCSW). As she stepped down in November, Ginny transferred a district that has grown in membership through quality educational opportunities, a monthly speaker series and unique social events for networking and enhancing the clinical community. In the 30+ years, Ginny has balanced a busy private practice with this important volunteer position.

Ginny’s interest in Social Work began during the Kennedy and Johnson era when the culture asked, "How do I give back to my community?" For Ginny, her job as a clinical social worker has been more of a "calling” as it is so much a part of her life and identity.

Ginny’s early interest in mental health began with close relatives that had medical issues that appeared to be exacerbated as stress escalated. This raised her curiosity about the impact of pressure and stress on one’s wellbeing. Her early work focused on understanding the interplay between physical and psychological health to help the people she was treating.

A National Institute of Mental Health Fellowship funded her graduate education at the University of Buffalo School of Social Work, within commuting distance from her home in Rochester, New York. After receiving her MSW, she joined 125 other Clinical Social Workers at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. This is the Harvard teaching hospital focusing on learning that provided rigorous training programs and weekly two hour individual clinical supervision. As a Social Worker in the Department of Psychiatry In-Patient Unit she worked with the psychiatrists in a team to treat patients in a “therapeutic community” approach as defined by Maxwell Jones. In Boston, Ginny also served on the Faculty of Simmon’s School of Social Work then later on the Faculty of Smith School of Social Work supervising social work students.

After relocating to Washington, D.C. with her husband, Ginny was recruited as a Senior Consultant in the Consultation and Education Unit at the Woodburn Center for Community Mental Health in Fairfax, VA. The Woodburn Center was an early leader in developing a new model in community mental health centers. There she developed a new consultation program for the District Court Judges who made commitment decisions. She also continued her clinical practice in the out-patient unit. Her cohorts of psychodynamically oriented social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists provided extended high-level training and consultation. With the advent of licensing, she developed a private practice in Virginia as well.

Ginny joined the Society for Clinical Social Work in the D.C. area and soon connected with a wide variety of fellow clinicians. She had many networking and extended learning opportunities through the Society and soon understood the unique value of a strong organization.

Ginny moved to the Bay Area in 1982 and immediately joined the California Society for Clinical Social Work. The Society enabled networking and educational connections with Bay Area social workers. The Mid-Peninsula District of the California Society for Clinical Social Work has been very fortunate that Ginny found them---providing many years of quality educational speakers and professional networking opportunities to the members.

Ginny's parting advice and thoughts for new clinical social workers are:

- Find the absolute best training and supervision you can.

- Continue learning throughout your career.

- Keep involved and connected with all of your fellow professionals.

Community, connection, and education have been front and center to Ginny Frederick's life and career in clinical social work. These three things have guided her work—and fortunately for us, guided her leadership as the coordinator of the Mid-Peninsula District of the California Society for Clinical Social Work for over 30 years.

Bipolar, Not So Much: Understanding Your Mood Swings and Depression

Bipolar, Not So Much: Understanding Your Mood Swings and Depression

by Chris Aiken, MD, & James Phelps, MD, W. W. Norton & Company, New York, NY, 368 pages, $22.95 Hardcover

(https://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/reviews-commentary/book-review-bipolar-not-so-much-understanding-your-mood-swings-depression/)

This book review is reprinted with permission from The New Social Worker, Winter 2018

Reviewed by: Jodon English, LCSW

Bipolar, Not so Much, is aimed at those who experience, and those who treat depressions and the range of manias in the middle of the mood spectrum—more than unipolar, but not fully bipolar. Bipolar disorder, despite its current vogue in the vernacular, may be one of the most misunderstood and difficult-to-diagnose disorders we currently encounter. Its varied presentation, the tendency to present for treatment primarily at the extremes of either side of mood, the deep and common misunderstandings of mania and hypomania and the overlap of symptoms with many other disorders make an accurate diagnosis of bipolar disorder as difficult as it is important.

The idea of a mood disorder spectrum, as described by the authors, makes important headway toward the DSM’s stated but not yet realized goal of moving away from a categorical and toward a dimensional model of mood, key to accurately identifying where a person lies on the mood spectrum, which has vital implications for successful treatment.

Of particular note is the authors’ clarification of mania and hypomania, which addresses the commonly accepted but less commonly seen “classic” model of mania, the euphoric, confident, grandiose “high” of a mania that people are reluctant to let go of and so eagerly watched for by less experienced clinicians. Aiken and Phelps describe the restless, agitated, distressed, and anxious side of mania, often tinged with aggression and paranoia, that my colleagues and I in community mental health see far more often than the classic mania or sunny hypomania intake clinicians often screen for.

The authors give many more diagnostic tips and tools. Presented primarily to help clients gain an understanding of their place on the mood spectrum, these tools have already found their way into my own thinking and practice. The book is aimed primarily at clients, but the level of writing and scholarship is such that students, beginning social workers, and even seasoned ones will find much of value. The research is quite current, and the authors are advancing the body of knowledge, with a great deal of valuable “practice-based evidence” drawn from their treatment of those on the mood spectrum.

Early chapters serve to define the disorder and educate the reader, with later chapters presenting clear and effective strategies and tools for managing it, including chapters on sleep, exercise, diet, and therapies. Much of the book discusses medication, and although I found the information both useful and interesting, there is a dizzying plenty of it. This, and the high level of the writing, make the work appropriate for the more sophisticated lay reader. However, the tone is hopeful and encouraging, imbued with compassion and leavened with humor when appropriate.

Overall, this book is accessible to the person who experiences these conditions, but with enough depth and rigor to be engaging and valuable to clinicians. I have recommended it to several colleagues, will prescribe it to several clients, and have awarded it precious space on my clinical shelves.

Jodon English, LCSW is in private practice in Pasadena. He can be reached at (213) 925-8170 jodonenglish@gmail.com and https://www.jodonenglishtherapy.com

It's Not About the Sex: Moving from Isolation to Intimacy after Sexual Addiction

It's Not About the Sex: Moving from Isolation to Intimacy after Sexual Addiction