THE CLINICAL UPDATE | SUMMER 2021

Membership renewal for fiscal year | Upcoming events

|

Letter from our President, Amanda Lee, LCSW

What comes to mind when you think of “balance”? If you have been following the summer Olympic Games in Tokyo, like I have, your brain might conjure up the image of a balance beam, and upon it, the gymnast who has sparked a spirited discussion about more than just her routine. It’s not the first time during the pandemic that a high-profile athlete has put their mental health and well-being above socially sanctioned manifestations of success. Afterall, we worship at the feet of gold, silver and bronze idols. An invisible force, mental strength, the ability to stay calm, execute, and overcome under immense pressure, oftentimes to the detriment of self, is celebrated, and scrutinized when seemingly absent or lacking. On Instagram, the same gymnast wrote, "For anyone saying I quit, I didn't quit. My mind and body are simply not in sync… I don't think you realize how dangerous this is... Nor do I have to explain why I put health first. Physical health is mental health.” Take a moment and let that statement sink in.

As practitioners, our clinical training has taught us that rather than it being “all-or-nothing”, mental well-being is a delicate balance that our clients, and indeed, all of us, work on throughout our lifetimes. Many of us practice from a holistic framework that is centered on the balance of mind-body-spirit. Certain events, developmental milestones, crisis points and underlying conditions will undoubtedly challenge that balance. Sometimes, despite our best efforts, we lose our footing and fall off the beam. In fact, the irony is, we need our mental fortitude to be tested in order to foster critical thinking skills and personal growth. It isn’t so much about striving for the absolute absence of fear, weakness or uncertainty, but rather, recognizing our inherent vulnerabilities and learning and choosing to manage them in a way that we honor our integrity and worth. We are reminded that we aren’t alone in our struggles, and of the benefit of reaching out to others, our “team”, for support. For our clients, we are a part of that team of people who believe in their potential, respect where they are at and where they want to go, and who prioritize their well-being.

The last 18 months have been an unrelenting gauntlet of navigating the unfamiliar. Do we use telehealth? Is telehealth effective? What platform is best? What if my clients don’t have access? Do we go back into the office? Do we keep paying for our office space? What about racial justice? Should we wear masks? Should I just retire? Should we ask our clients if they’ve been vaccinated? Am I safe? It’s been an endless barrage of more questions than answers. Then, there has been tremendous grief and loss that we have experienced in parallel with those we serve, with little opportunity to process, and the impact has been noticeable. While our clients face uncertainties around their health, finances, relationships, careers, academics, etc., exacerbated by social and political unrest, clinicians continue to grapple with impossible decisions around how to balance practicing safely, ethically, legally and effectively. The way we conduct psychotherapy, provide services, assess, relate, attach, explore, empathize, heal, restore, has required us to pivot, sometimes unsteadily, braving different approaches. The reality is, we don’t need to be an elite athlete to feel as though balance is a difficult goal to achieve, especially at this time in human history.

The gymnast didn’t quit. She recalibrated and asserted her priorities. She sought and accepted support. She did the work, did her best, did what was within her power to do. She got back on the beam, on her terms. She won a bronze medal. Truly, the last point is nugatory, but it’s what we are tempted to focus on. The greater message describes the process in getting there. Despite recent setbacks announced regarding the state of reopening, among other continued struggles, we are all doing our best to get there too. The California Society of Clinical Social Work (CSCSW) hopes to be there for you, as your professional community of support and encouragement, along this journey. Thank you for your continued membership, it is a sign of your commitment to professional self-care and well-being. As a member of CSCSW, there are a multitude of benefits that we hope you will explore and take full advantage of. You are part of a proud contingent of clinical social workers and affiliates dedicated to the art of hope and healing. Your prioritization of health and wellness in the work you do advocates for their value in our society.

CSCSW The Art of Psychotherapy: The Therapeutic Alliance, Beginning, Middle, and End

By Dr. Wanda Jewell

Thank you for the amazing opportunity to do the Art of Psychotherapy series. For me it is a culmination of my education, experience, and especially, all my years of teaching, and using all of it to give a useful and nourishing series. I thank my teachers, students, and clients for helping me learn.

Dr. Tanya Moradians has been instrumental in designing the series and inviting my participation. We partnered in the desire to provide workshops on psychodynamic theory and practice to beginning clinical social workers as well as experienced clinicians since the schools of social work have moved to evidence based practice and are no longer teaching psychodynamic work.

During the pandemic we were able to move to a state wide webinar with skilled tech and admin support from Donna Dietz, and have gained quite a following.

In the 10 session series, we are discussing the therapeutic relationship, beginning, middle, and end. We have just completed workshop #7 on the middle phase. We will have 2 sessions on termination and evaluation, then the 10th session will be a summary and wrap up.

The model we are using is a webinar format with Dr. Tanya and a few other talented clinicians as a ‘front row panel.’ When beginning to plan the webinar series I knew that I could not stare into a camera talking about relationship! I need to see other people! Donna allowed me to invite panel members to be visible during the talk and for the discussion.

This model works very well. It is a way of demonstrating relationship while we are discussing relationship. The trust and rapport that has developed among us-Tanya, Donna, the panel, and myself, allows true safety and true creativity. We have fun and it seems our audience also enjoys and participates in the good info and the good feeling we create each time. It parallels the therapeutic rapport in that it allows each of us to relax, be who we are, and share deeply of our knowledge and experience. There is no substitute for feeling safe and supported. Thank you panel!

The panel is a little different each time, depending on who can attend. They are: Mike Foster, Mario Espitia, Deborah Villanueva, Cindy Chen, La Shonda Coleman, and Lauren Eccker. All are clinical social workers with a broad variety of perspectives. If I added their many credentials and experience this writing would be double in size. Feel free to look any of them up on CSCSW website.

Our format is that after introductions I speak on the day’s topic, and after a break the panel members each comment on the topic, then we open to Q & A with the participants. Each workshop is 2 ½ hours.

About my background: My MSW is from USC School of Social Work, 1987. I spent 5 years as a Psychiatric Social Worker at Metropolitan State Hospital. Then I worked many years as Family Therapist and Clinical Supervisor in addiction treatment agencies. I earned the PhD in Clinical Social Work from the Sanville Institute in Berkeley, 2008. And, from 1998 to 2021 I taught at USC School of Social Work.

My early training in psychodynamic social work emphasized the developmental nature of the therapeutic relationship, beginning, middle, and end, with tasks for the clinician in each phase. This is what I present in the workshops, rounded out with my years of experience and education.

Psychodynamic theory makes sense to me. There are 4 aspects to this work, that if you are aware of these and working with these, you are doing psychodynamic work. 1. The past influences the present, 2. behavior is often driven by unconscious motivation, 3. People utilize defenses to protect themselves, and 4. Transference and countertransference, client and practitioner projections, often occur in the therapy.

All of these aspects are discussed in depth in the workshops, and include Attachment theory and neurobiology, stress and trauma, and how the patterns people learn in childhood are carried into adulthood.

I am delighted to share my experience and knowledge with other clinicians, wherever they are in their education and careers. Thanks again for the opportunity. This series means a great deal to me. I am happy to participate as our profession changes and with the hope that the field will return to an emphasis on psychodynamic work. We may find as we evolve that techniques may help people heal but only within deep connection to another in the therapeutic alliance. We believe that healing occurs within the “Art of Psychotherapy.”

Please note that all of the workshops have been recorded and are available with the powerpoints and handouts thru the CSCSW website.

Wilderness as Therapy: Current & Future Directions

By Erika Wadsworth

Wilderness Therapy, sometimes known as Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare, is an evolving treatment model that combines evidence-based therapeutic modalities with expeditions into the wilderness. Structure, philosophical approach, and even daily activities can be quite varied across different Wilderness Therapy programs; what unites them is the use of the challenges and metaphors of nature as tools for psychosocial healing, insight, and reflection. While there are some reservations to consider, I believe that incorporating wilderness experiences into therapy can provide rich opportunities for clinical development and growth.

Wilderness Therapy expeditions emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, influenced to a large degree by the popularity and success of organizations such as the Boy Scouts of America and Outward Bound (White, 2015). Wilderness Therapy programs built on the outdoor education model by adding licensed therapists to their staff, thereby bringing a clinical focus to the work and enabling them to serve higher-risk populations. Today, some Wilderness Therapy programs include equine-assisted or canine-assisted therapeutic activities. These activities allow clients to interact with animals in an organic manner–including by petting, training, and feeding–and use these interactions as a metaphor and catalyst to work through emotional and behavioral challenges (Brennan, 2021). Even outside of formal Wilderness Therapy programs, some clinicians have found that incorporating “walk and talk” therapy–where clients can practice mindfulness in nature, exercise, and participate in therapy simultaneously– to be beneficial in a myriad of ways (Birthistle, 2017).

The psychological benefits of nature are well-researched and in many ways simply common sense. Studies show that time in nature reduces stress and provides a calming, therapeutic effect (ANFT, 2020). Recognition of the healing aspects of nature has led to the rising popularity of the Japanese concept of Shinrin–Yoku, or “forest bathing,” which involves spending intentional time observing and appreciating the natural world (ANFT, 2020). Further, the positive, durable effects of exercise on depression and cognitive functioning are well established (Fernandes, Arida, & Gomez-Pinilla, 2017). However–as important as these benefits are–the power and promise of wilderness as a clinical tool extends beyond these components.

Clinically relevant aspects of the wilderness as a therapeutic environment also include interpersonal cooperation, self-reliance, challenge and risk, and the concept of an expedition, journey, or quest for self. In the wilderness, clients must learn to work together, respect others’ boundaries and enforce their own, build and maintain healthy relationships, and both give and receive feedback. As such, many of the rich opportunities for growth presented in day-to-day wilderness living parallel those within the family–as well as school, work, and friend groups. As I have seen in my work as an associate wilderness therapist, this creates the potential for clients to develop transferable interpersonal skills, deepen their self-knowledge and confidence, and nurture a healthy relationship towards trust.

While Wilderness Therapy is a fascinating field, there are some areas that require greater attention and development if its potential is to be fully realized. For instance, while research on Wilderness Therapy is promising, it is limited (DeMille, 2018, OBHC, 2014). Treatment approaches differ widely across programs, making it difficult to produce generalizable studies. Further, much of the existing research has been conducted by advocates of Wilderness Therapy, potentially leading to bias (Berman & Davis-Berman, 2006). The lack of standardization across programs also raises concerns about safety and best practices within the field, although the Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Council is attempting to address this concern (OBHC, 2014). The exorbitant pricing of many programs, which is worsened by the lack of insurance coverage, impacts equitable access to services. Finally, some Wilderness Therapy programs employ various levels of coercion, up to and including physical restraint, that must be evaluated in light of the social work value of self-determination (Berman & Davis-Berman, 2006).

Overall, my short time working in Wilderness Therapy as a clinician has made me optimistic about the potential, as well as the current and future direction, of this area of practice. Clients often arrive at Wilderness Therapy when they or their families feel they have run out of other options, and I have had the privilege of working with many clients who experienced profound therapeutic breakthroughs in the field. For those who are interested in learning more, relevant resources on incorporating wilderness in therapy include The Anatomy of Peace: Resolving the Heart of Conflict by the Arbinger Institute, Will White’s Stories From the Field podcast, and the Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Center publications website, which hosts a growing body of research. Please also do not hesitate to reach out to me with any questions.

References

Association of Nature & Forest Therapy: Guides and Programs. (2020).https://www.natureandforesttherapy.earth/about/the-practice-of-forest-therapy

Berman, D. & Davis-Berman, J. (2006). The promise of wilderness therapy. Connecting With the Essence: Proceedings from the Fourth International Adventure Therapy Conference.

Birthistle, I. (2017) Green care and walk & talk therapy. Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 8.

Brennan, D. (2021). What is equine therapy and equine-assisted therapy? WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/what-is-equine-therapy-equine-assisted-therapy

DeMille, S., Tucker, A.R., Gass, M.A., Javorski, S., Christie VanKanegan, C., Talbot, B., Karoff, M. (2018). The effectiveness of outdoor behavioral healthcare with struggling adolescents: A comparison group study. Children and Youth Services Review, Volume 88. ISSN 0190-7409,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.015.

Fernandes, J., Arida, R. M., & Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2017). Physical exercise as an epigenetic modulator of brain plasticity and cognition. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 80, 443–456.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.012

Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Council. (2014).https://obhcouncil.com/research/

White, Will (2015). Stories from the field: a history of wilderness therapy. Wilderness Publishers. ISBN 13: 978-0692512432.

Erika Wadsworth, MSW, CSW holds a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of California, Santa Barbara and a Master’s degree in Social Work from San Diego State University. She is also a graduate of a fifty-day Outward Bound instructor development course in sea kayaking, mountaineering, and wilderness medicine. After completing her education in 2020, Erika began working as an associate therapist for a wilderness therapy program in Utah’s high desert. Her past experience includes work with displaced populations, first-generation college students, and people struggling with addictions. Erika can be reached at erikawadsworth@gmail.com.

The Art of the First Client

By Barbara Griswold

Since the start of the pandemic, many therapists have seen a surge of potential new clients in need of support. And with the shift to telehealth, the onboarding of new clients has become more complex, since all tasks need to be accomplished at a distance.

Your first contact with any client is part skill, part art, and all about balance. You need to allow the client to tell their story, showing the empathy that will sow the seeds of connection and rapport. This starts a good clinical relationship, and at the same time increases the chance the client will show up at the first session. However, you may not want to do a full-blown therapy session on the phone. Plus, you need to quickly accomplish tasks related to clinical screening and finances.

Below are 10 Tasks of the First Call, with some sample phrases:

1) JOIN. Sound warm and upbeat. Give hope and praise.

- “I know it isn’t easy to make the first call and reach out for help. I’m so glad you called me.”

- “Have you been searching a long time for a therapist? I’m sorry. It shouldn’t be so hard to find a therapist. I really admire your persistence.”

2) BRIEF SCREENING: Are the client’s issues in the scope of your competence?

- “Before we set up the appointment, it would help to know a little about the issues you are dealing with, so I can get a sense if I might be a good fit for you. In a few sentences, can you give me an idea of what is going on that has made you decide to get counseling right now?”

- After client tells story and you ask follow up questions: “I’m sure you’ve just told me a small portion of the story, but already I can hear you’ve really been through a lot, and that you are dealing with a lot of stressful things. I’m so glad you reached out — there is no reason you have to go through this alone.”

- “From what you’ve told me so far, your issues are ones with which I have a lot of experience, that I help clients with every day. So, I’d be happy to set up an appointment for us to meet and see if it feels like a good fit.”

3) THEIR QUESTIONS.

- “Did you have any questions for me?” “Oh, yes, that’s a great question…” In my experience, individual clients most often ask about my therapy approach, while couples most often ask what my success rate is at saving relationships. Practice some answers for these questions, using non-technical language.

4) FEES/INSURANCE. Fees must be clear before the client walks in the door.

- “So, before we pull out our calendars, let’s get boring business stuff out of the way. The charge for the first session is $___ and then after that for a ___ minute session is $___. Do you have insurance that might help cover this, or will you be paying yourself?”

- If you are not a provider for their insurance plan, or they don’t have insurance, and the client indicates they can’t afford your full fee: Say, “I understand. How much do you feel you could afford?” then negotiate an affordable fee or refer them elsewhere. You may also say, “while I’m not a provider on your insurance plan, many PPO or POS plans will give some reimbursement when you see any licensed provider. Or might you have a FSA, MSA, or HSA plan at your work that would help pay for your expenses?” At this point, if you really want to land this new client, you can offer to check coverage for them. Or you could say, “you may want to call your insurance and check your out-of-network reimbursement benefit for telehealth/in-person sessions. You would pay in full at the session, and I would give you an invoice to submit to your plan for reimbursement.”

- If you are a network provider for their insurance: “Well, good news! I am a preferred provider for your insurance, so I will take care of the billing for you, and you may only have to pay a copayment. I’ll need to call your insurance before we meet to check your coverage.”

5) AVAILABILITY:

- “Let’s look at scheduling. I have these openings…”

6) WHERE YOU’LL MEET

- If in-person: “My office is located at ________. Do you need directions?”

- If telehealth: Give client the video link or tell how they will get it.

7) CANCELLATION INSTRUCTIONS

- “Great! Now, if you do need to cancel, please e-mail me/call me with as much notice as possible. My cancellation policy is ___________. Also, please give me your e-mail/phone number where you’ll be on that day in case I need to cancel.”

8) INSURANCE INFO (IF APPLICABLE):

“So, before we hang up, why don’t you get your insurance card, so I can check your insurance before our first session?” (You can also have the client send a picture or copy of the front and back of their card via secure email). Note: In my book and Practice Forms Packet, available at www.theinsurancemaze.com/store, I have a “Checking Coverage: Essential Questions” handout which gives you the questions to ask the plan when you call.

9) CONFIRMATION AND FINAL INSTRUCTIONS:

- “OK, so let’s confirm: Our appointment is on _______ date and ________ time.”

- “I’ll be sending you some forms to fill out [say how you’ll send]. It is really important that you complete and return them before the session.”

10) CLOSING:

- “Any final questions?”

- “It’s been so nice talking to you, and I’m so glad you called for support. I’m looking forward to meeting you and to working together.”

One final recommendation: Even if you make first contact by email, talk to the clients on the phone before they come in. In addition to helping you screen for client appropriateness, this direct connection will decrease the chance of a no-show.

Barbara Griswold, LMFT is a private practice coach, and the author of Navigating the Insurance Maze: The Therapist’s Complete Guide to Working with Insurance – And Whether You Should, now in its 8th edition. In addition to her 30-year private practice in San Jose, she provides consultations and trainings to therapists nationwide with questions about insurance, progress notes, and the business side of their practices. She offers CE courses about documentation and insurance at www.theinsurancemaze.com, and invites you to contact her or join her mailing list.

Ethical Care of Your Practice and Yourself

By Ann Steiner

By Ann Steiner

Were you taught about office policies, setting and raising fees, professional wills, and other business/practice related topics in graduate school or your field placements? If you are like most of the clinicians I work with, these important, yet challenging topics rarely were addressed, much less taught.

Most social workers discover that CSWA’s Ethics Codes require that they have a plan in place for the disposition of their practices in the event of an unplanned absence or the equivalent of a professional will, years after they are already in practice. The time to deal with this is now. Not only is it easier to write out a thoughtful plan when you are not in crisis, it will clarify your treatment values and help you see aspects of your professional life that you may not have considered.

COVID has been a wakeup call and reminder that we all, regardless of age, health and socio-cultural location, need to have backup systems in place.

It is never too early to plan for the unexpected. We all occasionally get sick or have family emergencies, and eventually we will no longer be able, or wish to continue practicing. The ethical and clinical importance of planning for our temporary and permanent absences is often neglected.

What is the Therapist’s Professional Will?

The professional will is a document detailing your wishes for the continued care of your patients in your absence, whether planned or unplanned, from losing your voice to serious illness, relocation, retirement, or death. It is designed to reduce the trauma and impact on your patients, colleagues and yourself when you are unavailable. For example, when you have unplanned absences, your professional will addresses the following questions:

- Who will cancel, follow up with, and/or make referrals for your patients?

- Who has essential diagnostic and risk-related patient information?

- Who has your voice mail access code and appointment schedule?

- Who has access to your office keys, Zoom account, patient contact information and other details needed in an emergency?

- What will happen to your practice?

- How do you want your patients and their records handled in your absence?

These are not simple questions; there are clinical and ethical implications.

For example, do you really want your life-partner to be the main contact person if you are in Intensive Care? Plus, it is important that your attorney make sure your wishes are consistent with your estate plan. A professional will minimizes the risk of your patients feeling and being abandoned when you are gone. Often when a therapist dies, patients feel traumatized, which can get in the way of developing a trusting relationship with another therapist. Discussions in the workshops I lead often revolve around these nitty-gritty questions.

Prepare for Unexpected Absences

The process of creating your own therapist’s professional will builds community and eases the stress and burden on your family members, colleagues, and others during a difficult time of crisis or perhaps loss and grief. Putting together your own professional will removes the guesswork, confusion and headaches that often accompany unexpected events in our lives that make us unavailable to our patients.

Writing a professional will is much more than just creating a simple back up plan. The Emergency Response Teams I encourage clinicians to create often serve the dual function of being a consultation group during crises. A comprehensive will that truly protects yourself, your patients, colleagues and family, requires that you make some challenging personal, clinical and ethical decisions. It also helps you begin or continue with your long-range retirement planning.

While the concept of creating a professional will resonates with most helping professionals, the prospect of putting one into place can seem daunting. Building your own professional will can be a challenging, rewarding and important process. If you are like most therapists, you agree that this is an important project, yet it keeps sliding to the back burner. By making the commitment to work on this important clinical and ethical project, creating a system to handle your practice in your absence, you will gain peace of mind knowing that you have done everything possible to assure continuity of care for your patients.

Over the years the feedback I hear from workshop participants is that it was too difficult for them to follow through on this project on their own. A number of years ago the American Group Psychotherapy Association had T-Shirts that said “We Do it in Groups!” From participating in a hands-on professional will workshop, to forming your own Emergency Response Team, groups help. So, join us in January for a 6-hour Law and Ethics workshop to create the first draft of your professional will!

Save the Date!

What: The Ethical Care of Your Practice and Yourself with Ann Steiner Ph.D., LMFT, CGP, FAGPA

When: Saturday and Sunday, January 8 & 9, 2022 | 9:00 am - 12:00pm each day

Where: Online/ virtual

DESCRIPTION

This 6 hour Law and Ethics webinar is a deep dive, hands on workshop about the Therapist’s Professional Will. COVID has been a wakeup call and reminder that we all, regardless of age, health and socio-cultural location, need to have backup systems in place. Illnesses, retirement, relocation, sudden emergencies, and death happen. Plus, the Ethics Codes for every discipline require that you have a Professional Will. This workshop helps you plan who will contact your patients if you cannot, and ways to minimize the impact of your absence on your patients, colleagues, and community. All levels of experience welcome!

Ann Steiner Ph.D., is a Certified Group Psychotherapist, licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and consultant in private practice for 30 years. She pioneered the creation of the professional will, has published over 20 articles on the subject, consults to and presents workshops to clinicians throughout the US and in Europe, and has published two books about leading groups. Dr. Steiner served as an Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Psychiatry, UCSF, for 14 years; is on the faculty of the Psychotherapy Institute; and is a Fellow and member of the American Group Psychotherapy Association’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Task Force.

To read more about the Therapist’s Professional Will or learn about Dr. Steiner’s downloadable Therapist’s Professional WillÔ: Guidelines for Managing Planned and Unplanned Absence check out: www.PsychotherapyTools.com http://www.psychotherapytools.com/profwill_what.html Currently she is writing a manual titled: Your Therapist’s Professional Will: The Ethical Care of Your Practice and Yourself Workbook and Guide.

BCMH, Where I belong

By Elizabeth Hua

By Elizabeth Hua

Founded in the height of the pandemic, Bilingual Chinese-speaking Mental Health (BCMH) represents a place of belonging for me. BCMH is a virtual space on Facebook where mental health professionals and non-professionals can gather to share and consolidate resources, build community, and discover how to meet the mental health needs of this unique population from a cultural context. Although one does not need to identify as Chinese-speaking or a professional to be part of this group, the main focus of the group is for mental health professionals to gather and share their expertise with one another. Since its foundation, the group has given its members opportunities to connect with professionals throughout the U.S. and globally on platforms such as Zoom to network, identify concerns, and share helpful resources. A peer support mentorship program has been launched, where the purpose is personal development and connection between peers of the Facebook group. In this program, members can give and receive career, academic, and other general support from one another.

Though only 6 months old, the group is home to a total of 123 members, has shared over 20 resources, identified areas that have need for improvement such as clinicians’ cultural and language barriers impacting treatment, highlighting not only a gap in locating relevant and effective interventions to serve this population, but also a need for peership among bilingual mental health professionals.

When naming the group, I used the term “Chinese-speaking” to emphasize that Chinese is not only a language spoken by Chinese people, but also people who live in other parts of Asia and in other countries, thus adding to the richness of the Chinese language and culture. For instance, growing up in San Francisco, California, one may expect to not feel alone as an Asian American. The truth was far from reality for me—there was always an overwhelming sense of loneliness creeping over me when trying to navigate my identity as a Chinese Asian in North America born in an immigrant family. As a child, my weekly routine included activities such as translating documents from English to Cantonese for my parents when I got home from school and limiting my emotional expressions to what was appropriate for my family culture. With this being said, there was a constant separation of spaces when it came to how I could show up in the world. At specific times of the day, I show up as “American,” “immigrant,” “Chinese,” “English,” and more. It would not be surprising that my experience is common as well as distinct from folks who are from different parts of the country and the world.

Though this compartmentalization of space is not a new discovery, the pandemic allowed me time to reflect on the larger society and the impact of globalism, imperialism, and colonization on the Chinese-speaking community. Since English-speaking Europeans were the main colonizers, other cultural languages were suppressed and only English was allowed to be institutionalized in North American land.

In highlighting the importance of language, in Chinese, there are two primary translations of mental health: “精神健康” or “心理健康.” The first phrase broken down means spirit health, and the second phrase means in the heart. Yet in English, mental health points to the brain or one’s thoughts. This example alone should show how important it is to involve both English and Chinese into the topic of mental health, as the language itself is the key to our Chinese-speaking clients’ problems. The language also reveals the need for sophistication when thinking about health, that it is not just physical health, spiritual health, brain health, but also health inside the heart. Chinese medicine emphasizes the collective body, one body part affects the other; hence, we must take care of all parts of our bodies.

In the Chinese translations of mental health, each word has its distinct emotion and meaning that can lead the way in a therapeutic setting. Through the bilingual provider’s exploration utilizing the client’s native language, the client can then receive adaptive signals to help move forward and process emotions in a language which the body is familiar with and may find comfort in. There may be the presence of shame, guilt, and betrayal when we use English or Chinese with clients—because none of the languages feel truly authentic. This would be our own countertransference as mental health professionals who grew up hearing or learning two languages. What if we use this countertransference to help our clients explore and develop self-awareness in a culturally safe and experimental space?

BCMH was formed as a result of the uncertainties that came with a pandemic, and I was inspired to finally create a space to decolonize my mind along with like-minded individuals and lessen the loneliness of living in my current city, San Diego, where Chinese-speaking folks are a minority. My hope was to collaborate with my virtual community to foster a space that gives us permission to be our culturally and linguistically authentic selves as mental health professionals often provide for clients and the general community. 6 months later, this hope has turned into reality and my feelings of gratitude and belonging have only intensified as time passed by. Without the ability to speak Chinese or a space to seek learning of Chinese-speaking language and culture, you and I risk losing the opportunities to develop life-changing therapeutic moments that could be experienced by the bilingual mental health professional and Chinese-speaking clients. Language is how we know who we are and where we come from. This virtual space is the first step in filling the needs of this unique and diverse population, and I look forward to seeing more interactions in the group and diverse community members join to develop more virtual spaces that foster authentic cultural and linguistic expressions.

Elizabeth Hua, M.S., APCC is a bilingual clinician at UPAC Counseling and Treatment Center, a community mental health clinic that specializes in Asian-diaspora, immigrant and refugee populations in the San Diego area. She also serves individuals anywhere in California through Life Enrichment Services, a practice located in Oceanside, CA (she can be contacted at elizabeth@lesmentalhealth.com). She provides therapy and case management in Cantonese and English. Elizabeth is the founder of Bilingual Chinese-speaking Mental Health Facebook Group in which she invites individuals to join, and has an Instagram (@identifywithliz) that offers therapeutic posts and stories based on evidence-based and educational trainings she has received, to increase access to mental health knowledge for the virtual community.

Can We Legally and Ethically Ask Clients if They are Vaccinated

By Mick J. Rogers, Ph.D., LCSW, MBA

Clinical social work has been at the cutting edge of empowering clients and providing safety during stressful times: HIV/AIDS and 9/11 especially. What we learned from those times can be useful now.

My opinion is that we have a primary duty to protect clients from harm. This means ensuring that the physical and emotional space we provide is safe.

Physical Safety:

In the case of a communicable disease that may be aerosolized, this means that we must protect the health of our client in the room, the clients that will share the room later and ourselves. Therefore, optimally, we should be fully vaccinated and the clients we see face-to-face in our office should also be fully vaccinated. Otherwise, we should see them online (or possibly, properly masked in a room with proper ventilation and filtering (perhaps when doing a brief crises assessment for an unvaccinated client.)) It is ethical to ask our clients if they are fully vaccinated so we can best assure all our clients of reasonable safety. It is also ethical to inform them of our vaccination status so they can make an informed decision to consent to either office based or Telehealth therapy.

This is ethically complex.

- Some clients have medical reasons to not, yet, be vaccinated (immune system problems like transplant, HIV/AIDS that is not yet controlled, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, etc.). We need to ask them in a manner that does not sound like a demand and help them explore their complex emotional response if there is any medical grey area about their situation.

- Other clients distrust government/vaccines and need reassurance that their decision about their body’s care is respected, but that there may be reasonable consequences to those decisions—like receiving online therapy instead of face-to-face.

- In addition, there are clients who will lie about their vaccination status to get the benefits of those who are fully vaccinated. Because it would be unreasonable to assume that none of our clients would lie about this, and the risk to others who share our office due to their misinforming us (especially to other clients who claim they are vaccinated when they are not), we would be prudent to ask for a copy of our client’s vaccination card before resuming face-to-face care. Under HIPAA, their physician, pharmacist or health department can not release this to us without a signed release. It would be less intrusive to ask the client to provide a copy, instead. If a clinician believes his clientele is likely to forge these documents they should seek out a unique ethics consultation.

- There are social justice issues. Access to vaccinations in some counties may depend on getting time off from work and having reliable transportation. We need to advocate for these clients and encourage them to advocate for themselves. There is also misinformation that undocumented residents are not eligible for free vaccinations and are at risk of ICE detaining them. We need to facilitate access to accurate information about the vaccine being free to all and the real level of risk of deportation when trying to acquire a vaccine

- Children are a special case. Currently, younger children can not yet be vaccinated and they are less likely to die from COVID and more likely to just be an asymptotic vector of the Coronavirus. On a case by case basis some young children might best receive Telehealth, while others should receive masked face-to-face care with proper ventilation and filtering of air. Some child therapy offices are large, well ventilated spaces. In agencies, some shared child therapy offices appear to be twice the size of a mop closet and share ventilation ductwork with a neighboring room. In those depleted agencies Telehealth would be safer.

Emotional Safety:

Emotional safety is a separate issue. This request about vaccination status and the documentation of it is rife for transference responses. While many clients will see this as reasonable and be assured that their LCSW is doing everything possible to keep them safe, other clients may see the question as controlling and our decision to continue seeing them via Telehealth as punitive. Some clients might comply too quickly and not explore the ambivalent feelings they have. These clients need us to slow the process down and actively promote their autonomy.

And, of course, there are the therapists' countertransference issues. Some of us might have unreasonable fears about treating fully vaccinated clients face-to-face, others may dread asking for reasonable safety information because of our fears of being perceived as too authoritarian or controlling. Most of us will have reasonable worries about how the variety of clients we see will respond/react to our efforts to keep our clients and ourselves safe.

BIO Information

Film review: LFG Film Review

By Kimberly Taylor

By Kimberly Taylor

The US Women’s National Soccer Team (USWNT) is ranked #1 in the world. Since 1991, they have won four World Cups, four gold medals, and eight CONCACAF Gold Cups. The USWNT has become iconic - their following growing immensely throughout their success, inspiring young athletes, and frequently found in any media. The World Cup final against Japan in 2015 had the highest number of viewers for any soccer match in US history. But in 2019, the USWNT made a different kind of history - making international headlines when all 28 members filed a lawsuit demanding equal pay.

LFG is a CNN documentary on HBO Max named after the team’s rallying cry. The film follows the team’s fight for equity, and their extraordinary steps to set a precedent not only in soccer, but also in athletics around the world.

The film, directed by Academy Award-nominated and Emmy Award-winning director Andrea Nix Fine and Sean Fine, highlights the progress the United States and rest of the world must make in addressing discrepancies in pay and workplace conditions based on gender discrimination. Players including Megan Rapinoe, Kelley O’Hara, and Jessica McDonald, as well as the athletes’ legal team provide shocking insight into the realities of being on one of the winningest teams in the world. Some players reveal having to work at Amazon during the off-season or being unable to afford childcare, as the women make a fraction of the US Men’s team, despite playing and winning more games and titles. While a typical bonus after the USWNT wins a game sits at about $8,500, the US Men’s team will receive a bonus over $17,000 per win. After winning the World Cup, the men’s prize is over $9 million, but the USWNT is awarded just $2.53 million.

The documentary also depicts the inferior working conditions the women work in, in comparison to their male counterparts. The USWNT players and their lawyers note a discrepancy in training facilities and fields, as well as amenities when traveling. For example, the US Men’s team usually flies on charter planes, while the USWNT more often fly commercially. Not only did the US Women’s team spotlight the differing standards in the athletic world, but their case became a powerful movement highlighting the disparities in any field.

Even with the attention to the inequality, it should be noted that there has been significant backlash responding to the documentary. When searching for this film, results are flooded with negative ratings and reviews on public forums, as well as some negative professional reviews, accusing the documentary makers of falsifying information. These reviews are notably mostly written by males. No evidence or credibility to these claims of falsifying information have been found, although US Soccer did refute the details of the documentary in a 17-post Twitter thread. While of course this does not mean that every male shares this point of view, or that anyone identifying as any gender could predictably have any specific reaction to the film, it does affirm the point that the documentary attempts to make - that further conversations and action need to be taken. It’s difficult to specify what must be done to resolve this issue, seeing as so many causes of the current women’s movements, such as #MeToo, continue to see so many setbacks. But continuing education and awareness, conversations with lawmakers, and fighting to create increased standards are invaluable to the movement. Doing so may increase progress towards ensuring equal pay and equitable work conditions for everyone, no matter your gender identification. As we continue these efforts, the US Women’s National Soccer Team remains an inspiring and fearless example in their effort to make permanent, effective change and set a new worldwide precedent.

Kimberly Taylor, MSW, PPS-C, is a social worker living and working in San Diego. She is passionate about embracing resiliency, encouraging growth, and maintaining meaningful connections with clients while maintaining human dignity in any population or field.

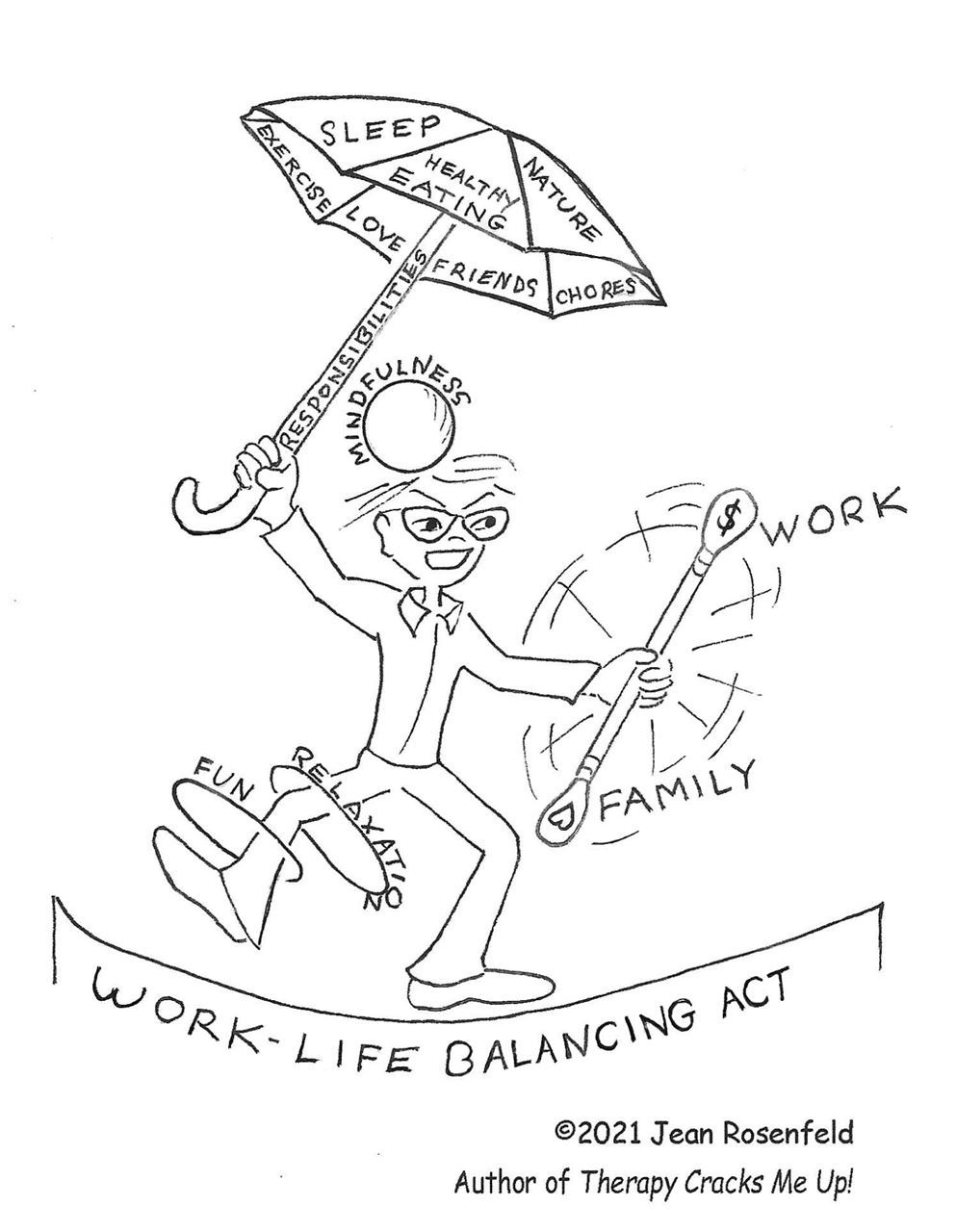

Work-Life Balancing Act

By Jean Rosenfeld

Jean Rosenfeld, LCSW is in private practice in the Sacramento area treating adults as individuals and couples. She has been involved with the Clinical Society for decades, as district coordinator, board member and former editor of this newsletter. Her book, Therapy Cracks Me Up! Cartoons about Psychotherapy, is on Amazon. She can be reached at Jeanrosenfeld@gmail.com

Jean Rosenfeld, LCSW is in private practice in the Sacramento area treating adults as individuals and couples. She has been involved with the Clinical Society for decades, as district coordinator, board member and former editor of this newsletter. Her book, Therapy Cracks Me Up! Cartoons about Psychotherapy, is on Amazon. She can be reached at Jeanrosenfeld@gmail.com

Update on BBS Liaison Role

The Board of Directors of the California Society for Clinical Social Work (CSCSW) would like to acknowledge and express our sincere gratitude to Natasha Singer, LCSW, for serving our members in the critical role of BBS Liaison for several years. Natasha’s contributions as the BBS Liaison have ensured that members with questions related to the BBS received personalized support and advocacy from CSCSW. Natasha has also served in other capacities on behalf of CSCSW, including as a board member, support group facilitator for ASWs and as a mentor.

The Board of Directors of the California Society for Clinical Social Work (CSCSW) would like to acknowledge and express our sincere gratitude to Natasha Singer, LCSW, for serving our members in the critical role of BBS Liaison for several years. Natasha’s contributions as the BBS Liaison have ensured that members with questions related to the BBS received personalized support and advocacy from CSCSW. Natasha has also served in other capacities on behalf of CSCSW, including as a board member, support group facilitator for ASWs and as a mentor.

Natasha received her Bachelor of Human Services and Counseling from the State University of New York (SUNY - Empire State). She completed her master’s at SUNY Albany School of Social Work. Natasha spent many years working in agencies specializing in substance abuse, psychiatric and bereavement before opening her private practice. After moving to LA five years ago, Natasha brought her private practice to Studio City. While building her practice in Southern California, she worked as Clinical Director for Victory Detox in North Hollywood, with the Glendale Adventist Hospital Bereavement program, leading groups for suicide survivors and bereaved spouses and supervised AMFTs and ASWs for the Teen Project Inc. , as well as with Iris Healing Treatment Center for dual diagnosis inpatient substance abuse as a primary therapist.

Natasha is a certified Brainspotting practitioner, uses tapping, and somatic awareness and works psychodynamically. She specializes in Trauma and Grief and Loss. She works primarily with adults. Natasha sees things holistically - everything is connected – physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual. She teaches mindfulness, meditation, breath techniques, and yoga relaxation techniques.

As Natasha steps away from the BBS Liaison role, we greatly appreciate her for all that she has done and continues to do for CSCSW, and for her unique gifts as a clinical social work practitioner. We are excited to welcome Alicia Martinez and Sarah Jayyousi as our new BBS Liaisons and thank them for their time and dedication. Access to our BBS Liaisons is an exclusive benefit for members of CSCSW. If you have a question related to the BBS that you need support with, please contact CSCSW.BBS.Liaison@gmail.com.

Community poem: Song of Diversity

By Emma Gross

This world begs for diversity.

She knows it in her strange, blue heart, From the way the trees dance effortlessly When people from every sea

Stand beneath them.

Or from the way

Dragonflies hum

When they are

Surrounded by languages.

It is these differences that

Make the most courageous song.

A worldwide lullaby

Of origin, race,

Jokes passed down from mother to daughter To daughter’s daughter.

Different ways to pronounce

Tree,

Bloom,

Wing.

The innate righteousness of

Cultures brushing shoulders.

Of babies holding mixed stories in their bodies. This whimsical evolution made by

The way one person can love another,

Despite the three seas that separated their births.

Reminding us of

The commonality of being alive,

Together,

Now.

This song is necessary.

Urgent.

Must be sung

Until children can read to one another,

About different cultures,

And realize their stories are gorgeous either way.

This is the song of diversity.

With a chorus that sings our differences.

A melody that sounds like

What we believe in.

And instrumentals that are Who we become.

And until justice blooms, And we are all together singing, This song never stops

Until it is heard.

Emma Goss is a poet from Los Angeles. She has been writing passionate poetry ever since second grade, with special attention to topics of youth, race, culture, and family. Her poetry has been seen in the L.A. Zoo Beastly Ball, the foundation for excellence in education, and it has received an honorable mention in a poetry contest from Princeton University. As a rising senior in high school, Emma has received the Kenyon Book Award and is participating in the creative writing fellowship program at Campbell Hall High School, planning on studying creative writing in college. Emma's grandmother was one of the founding members of the CSCSW.

Emma Goss is a poet from Los Angeles. She has been writing passionate poetry ever since second grade, with special attention to topics of youth, race, culture, and family. Her poetry has been seen in the L.A. Zoo Beastly Ball, the foundation for excellence in education, and it has received an honorable mention in a poetry contest from Princeton University. As a rising senior in high school, Emma has received the Kenyon Book Award and is participating in the creative writing fellowship program at Campbell Hall High School, planning on studying creative writing in college. Emma's grandmother was one of the founding members of the CSCSW.

Thank you to our donor, Carmen Siddiqi!

By Amanda Lee

Thank You for Donating!

Over the years, the California Society for Clinical Social Work (CSCSW)has had the honor of reviewing a number of inspiring stories from students who want to make a positive difference in people’s lives through clinical social work practice. This is precisely why the Jannette Alexander Foundation for Clinical Social Work Education (JAF)was established in 1999. Each year the Jannette Alexander Foundation awards scholarships to master’s students from California accredited programs for excellence in clinical studies. Recipients receive an award of $1,000 each, plus a free year-long membership to the CSCSW. These resources go a long way in supporting new graduates in actualizing their professional goals. To read more about our outstanding 2021 scholarship recipients please refer to our website here.

The CSCSW Board of Directors would like to thank all who have generously given to this scholarship fund. We would especially like to recognize one of our emeritus members, Carmen Siddiqi, MSW, LCSW, BCD of Santa Barbara County for her substantial donation of $1,000. Carmen earned her MSW degree from USC and has practiced clinical social work for 46 years, promoting the health and mental well-being of field workers. She shared that the reason for her contribution is that it is important to continue to fight for representation in clinical social work practice. We celebrate Carmen’s contributions to the profession and thank her and others for continuing to support the integral presence of clinical social work in California.

If you are in the position to do so, we would truly appreciate it if you made a tax-deductible donation, of any amount, to help the CSCSW to continue this legacy.

Donations can be made by clicking here.

Real Talk

By Sarah Jayyousi

By Sarah Jayyousi

Colorism from an Ally’s Perspective

As a light-skinned woman immigrating to the United States, I have experienced my fair share of xenophobia, sexism, and prejudice. That being said, I can never claim to understand what it’s like to be a Black or Indigenous person of color (BIPOC) in the United States. BIPOC communities face a unique form of systemic oppression that differs greatly from the experiences of other marginalized groups, and much of this increased discrimination can be linked to “colorism,” a phenomenon that is closely tied with racism. Colorism refers to the increased privilege and value afforded to individuals with lighter skin, even within one’s own community. For example, the “paper bag test” refers to a colorist practice in which an individual’s complexion is compared to a paper bag in order to determine if they are afforded certain privileges; this is most commonly seen in the media, in which many television shows and movies are criticized for their exclusive portrayal of light-skinned actors and actresses, regardless of their racial/ethnic background.

Watching the news, there are daily incidents highlighting racism in our society, including the multiple instances of Black individuals killed by police. I ask myself what I can do to best support friends, family, coworkers, and others in my life who experience racism. Our country was built on oppression of Black and indigenous individuals and continues to maintain long-standing structural and systemic racial inequities. The prison industrial complex, for example, demonstrates severe racial inequity in which Black individuals are given longer sentences, are often falsely imprisoned, and face higher rates of police brutality. The racism that is ingrained within the carceral system also inevitably manifests itself within the educational system in the form of the school-to-prison pipeline, in which BIPOC students are suspended and expelled at higher rates than their peers, as well as many schools, with predominantly students of color, stationing multiple police officers and security guards on campus. Our school curriculum is biased and predominantly comes from a white, straight, male perspective rather than a diverse view that represents the real experience of BIPOC and minority groups. This practice further cements and perpetuates structural and systemic racism and lack of inclusivity in our educational system. Educators can increase awareness of rooted racism in our educational system and acknowledge the complexities of this system in K-12 and higher education.

Racism and prejudice are also seen in mental health and child welfare where Black individuals are more likely to receive a schizophrenia diagnosis and receive inadequate mental health treatment. They are also more likely to have their children removed from the home for the same circumstances compared with white individuals. It is necessary for us to examine and challenge our own subconscious tendencies that contribute to systemic racism, including colorist biases. When immigrating to the United States, I faced both immigrant and linguistic oppression, but due to my lighter skin I was still afforded more privileges.

And so, as someone in my position, I ask myself: What can I do as a non-Black individual to use a critical lens and to help dismantle racism? What can we all do to increase recognition of our white privilege and best support people of color? What can we do as Latinx/Chicanx, Asian, Middle Eastern, Muslim, Jewish, and/or LGBTQ individuals to recognize and combat colorism within ourselves and our communities?

We can’t simply claim to be “colorblind,” nor can we deny the significant impact of racism on our BIPOC allies. This so-called “colorblindness” perpetuates racism by encouraging us to ignore racist policies and social injustice. Furthermore, our own inherent colorism perpetuates systemic racism by preventing unity among marginalized communities.

Together, we can encourage each other to recognize our own role in maintaining the status quo and support one another in actively countering racism both within ourselves and within our own communities. As social workers in academia, clinical practice, mental health, child welfare and hospitals, we must ask ourselves what steps we can take to actively be anti-racist. On this ongoing journey of engaging in anti-racist practices, we must take ongoing steps to strive toward anti-racism and remain open to counter-stories and examine our own role in this systemic racism. We must take steps to influence and shape antiracist policies and systems. We must commit to ongoing examination of our own social values, biases and inherent prejudice and socialized racism. We can take responsibility to become better educated rather than relying on people of color to educate us about their stories and systemic oppression. As a social worker, educator and ally, I hope to take a critical lens and evaluate my own practice with students and clients and strive to practice anti-racism every day. I urge you to join me on this journey to actively engage in anti-racism and take an active role in supporting oppressed and marginalized individuals of color.

For anti-racism resources, please visit the following link from the Network for Social Work Managers (NSWM).

Sarah Jayyousi, LPCC, LCSW Sarah has over 25 years of experience in diverse settings, including intensive outpatient, inpatient behavioral health, non-profit organizations, and education. Sarah is a lecturer in the Master in Social Work program at California State University, San Marcos. She is very passionate about social justice issues and advocates for the utilization of the recovery model in helping individuals from diverse backgrounds. Sarah also serves on the board of the California Society for Clinical Social Work and co-chairs the Diversity, Equity and Transformation Committee.

Book Review of My Grandmother's Hands

By Karen Pernet, LCSW, SEP, RPT-S

My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies by Resmaa Menakem MSW, LICSW, SEP.

Citation Resmaa Menakem (2017) My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, Central Recovery Press, NV. ISBN:978-1-942094-47-0

The title of the book relates to the loving relationship the author had with his grandmother, the effects of racism on her and specifically refers to her hands which were “stout, had broad fingers and thick pads under each thumb”(p. 4) caused by many decades of picking cotton, starting at 4 years old. The author’s mother added that her feet also were wide, thick and calloused. An intense image: grandma as a barefoot little girl picking cotton in the fields, feet and hands bloodied and in pain! Throughout the book author’s image of being held as a little boy by grandma’s loving and thick, calloused hands serve as a powerful metaphor for the effects of racism.

Note: My Grandmother’s Hands focuses almost entirely on racial trauma, defined as between white European-Americans and African-Americans and law enforcement officers of all ethnicities.

This book is unique in its approach to racism: a somatic examination of the trauma of racism, historically, over the generations up to the present, including many personal examples; the goal is understanding the effects of the past on our bodies in the present so that deep healing can occur. Written by Resmaa Menakem, an African American therapist, LCSW and Somatic Experiencing Practitioner, his subject is looking at racism from an embodied perspective using somatic experiencing, trauma theory and polyvagal theory to examine white supremacy, the profound effects of racism on African Americans and specific issues of the police and law enforcement. He explores the history and internal experience of racism on whites/European-Americans prior to emigrating to the US, on African Americans and on the police and others involved in law enforcement. It is both logical and powerful that he refers to each group by color and physicality: “white bodies, Black bodies and blue bodies or police bodies,” given the focus on the internal effects of racism. The book has exercises in each chapter for the reader; the purpose is to experience the material in addition to reading it. There is also a helpful summary after each chapter

My Grandmother’s Hands is divided into 3 parts.

Part 1 Unarmed and Dismembered-Effects of trauma on our bodies…from white privilege combined with white fragility to the pain and cost of being Black in America to the effects of undigested trauma within police bodies and caused by them, especially to black bodies.

Part II Remembering Ourselves-Healing focusing on modalities to heal the embodied self. This part of the book is filled with helpful and specific ways to works with trauma, dissociation in general, not only related to racism. There are specific activities for white bodies, black bodies and blue bodies (police and law enforcement).

Part III Mending our Collective Body-Activism that is body centered and healing in group settings.

An essential part of the author’s premise is that there are two kinds of psychological pain caused by racialized trauma: clean pain which leads to healing and dirty pain which creates a state of ongoing and ignored pain and disconnection and that is reenacted on others or ourselves. Clean pain is doing the hard work of awareness, facing the trauma of our past and present, working through it with meditation, with therapy or body focused therapeutic activities and finding safe outlets for the energy that is released.

The author writes about fight, flight and freeze responses to repeated racialized trauma, that are embedded in our beings. He has studied with trauma experts such as Bessel Van der Kolk, Steven Porges and Peter Levine and uses their work as a basis for his approach. He renames the vegus nerve as the soul nerve and states based on research and experience “The soul nerve is not just where we experience our emotions, it is also where we feel a sense of belonging” (p. 156) In order to work through pain successfully, the person needs connection to others who are doing or have done this work.

Resmaa Menakem has strong beliefs about racism which some white readers may find challenging; however, this is not a book about blame. The goal to wake up those of us who are white to look at our privilege and our fragility that serves to protect us from facing the reality of the trauma that racism has caused in the US.

Blacks have been and are being affected directly and carry with them the stain of racism; their work is, in part, to deepen connection to themselves and within their communities as part of the healing.

Police are under continued stress which is very often not acknowledged as problematic and lay at the root of disconnection and destructive actions towards Black people.

My recommendation: As a white therapist trained in Somatic Experiencing, I appreciated the wisdom of this book and the exercises. As a reader, I found it challenging because of the time involved in the numerous experientials. A major premise of this work is the value of connection. Keeping that in mind, I think this would be an excellent book for a seminar, a consultation group or a book group. Sharing the experiences would deepen the meaningfulness. At the same time, it can be read alone, the exercises followed and a great deal gained. Finishing the book is important: Part 1 is the problem which we are asked to experience in our bodies through the exercises; Part II is the healing and the exercises are valuable for ourselves as well as our work with traumatized clients; Part III is not as strong but still has many useful ideas for social change combined with embodied methods of staying connected.

Karen is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker with over 25 years experience working with children, families and individuals, supervising and training. She is passionate about using play therapy and sandtray therapy as a healing modality with people of all ages as well as for supervising and training therapists. Karen is certified as a Play Therapy Supervisor, a Filial Therapist (Parent-Child Relationship Enhancement Therapy), a Gestalt therapist and a Somatic Experiencing Practitioner. She has extensive training in trauma and attachment therapies. She has published print articles on Filial Therapy and presented and trained throughout the US on play therapy. Karen is a co-founder of Growth through Play Therapy trainers and a provider for the Association of Play Therapy. She has a private practice in Oakland where she conducts intensive, small group trainings. Racism and diversity are personally and professionally important to her and she is currently developing a sandtray model to address culture in ways that bypass defensiveness.

About the Clinical Update

Editor: Janny Li, MSW, ASW

The Clinical Update publishes relevant, educational, and compelling content from clinicians on topics important to our members. Contributions and ideas for articles can be sent to Jannyli.msw@gmail.com -- please write "Newsletter" in the subject line.

Ad placement? Contact Donna Dietz, CSCSW Administrator - info@clinicalsocialworksociety.org

.png)

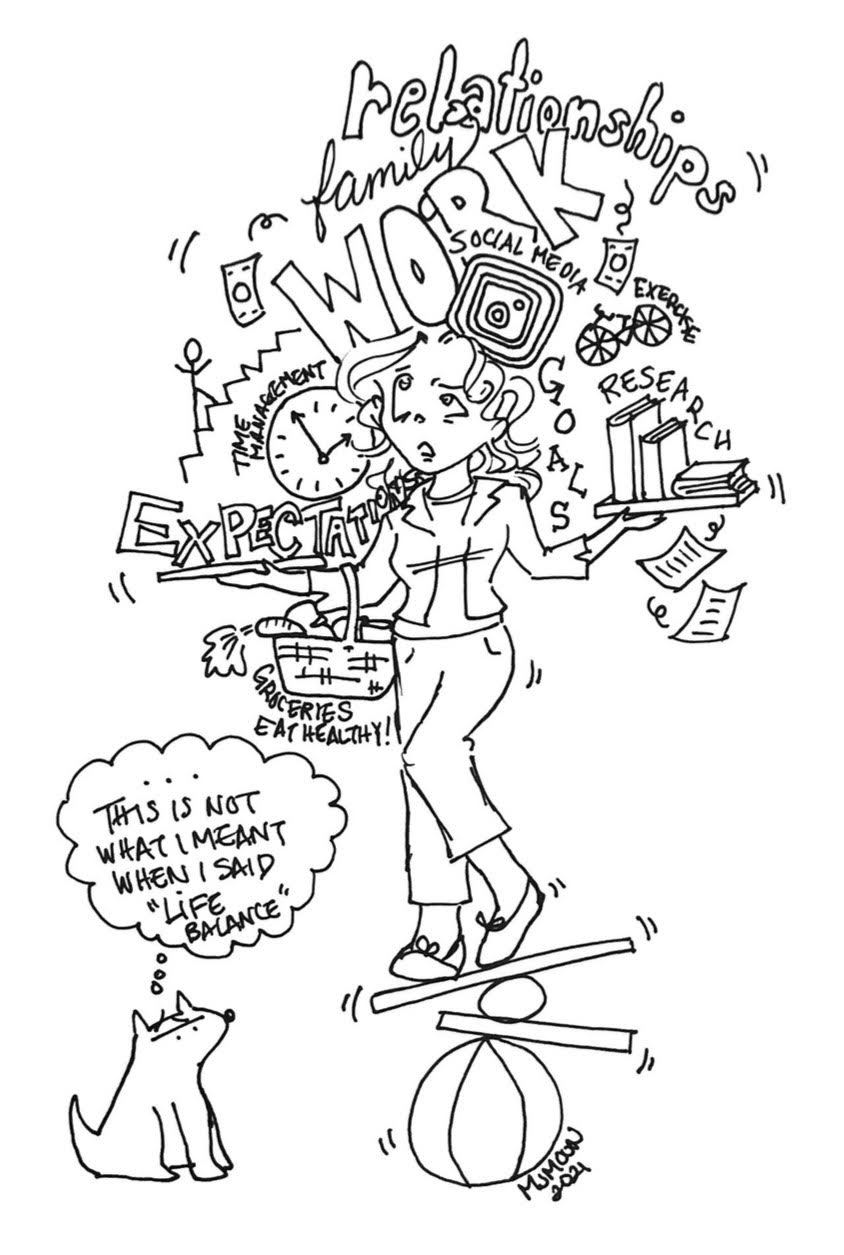

Monica Moon: Monica currently on orders in Norfolk for the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves and is actively interviewing for social work administration positions. She hails from San Diego, loves food, travel, and does a pretty good Cher impersonation.

Monica Moon: Monica currently on orders in Norfolk for the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves and is actively interviewing for social work administration positions. She hails from San Diego, loves food, travel, and does a pretty good Cher impersonation.